How to have solidarity with the sexually abused daughters of famous feminists

Andrea O'Reilly, an renowned expert on "feminist mothering," allowed her daughters to be sexually abused

I protected my mother’s identity for so long. I changed my name so that I could write freely without implicating her, and even then, I left out important details of my story because they could lead to her identity being discovered. I protected her because of my deep empathy and compassion for her; because I didn’t want to hurt her. I also hold a deep ethic of opposition to punishment and I don’t believe the internet is the right or best place to seek justice most of the time. But also — I was brainwashed. I was brainwashed by my family into submission. I was told over and over again that I had a feminist mother and I should be grateful. I was told over and over again that nothing really happened in my family, that the problem was not the incest or my father’s rage, but me and my trauma, my anger, my pain.

Last summer I reached a place where truth telling was a visceral necessity in my body. I was (and am) trying to get pregnant and yet it did not feel safe to get pregnant until the spell of unreality had finally been broken for good. I started to write about details I had never written about before, including the fact that my mother is famous scholar of “feminist motherhood.” And I started telling the people closest to me that I was thinking about naming her. Everyone in my life seemed to share the perspective that I shouldn’t name her — that I couldn’t name her. I was reminded of my own ethics about refusing punishment, of my very public opposition to cancel culture. I was reminded of the risks and the dangers, the potential drama. I was advised to find a way to make peace with my situation, to find a way to believe that I had said enough. Then — my mother discovered that I was writing about the fact that she is a famous scholar of “feminist motherhood” and she threatened to sue me. Now, there was pressure not only not to say more, but to say less. To walk back my hard earned truth telling. To be careful.

One of my closest friends at the time responded to my texts about wanting to name my mother by taking on the role of an authority — she told me that naming her would be martyring myself. She insisted that it would be foolish — crazy — to name my mother in the face of my mother’s threats. She spoke with certainty and condescension and encouraged me to go over my writing and make sure everything I’d said could stand up in a court of law. This (ex) friend of mine is not an incest survivor. She has never even been sexually assaulted. She has never been on the stand and interrogated by a defence lawyer. She has never been driven home in a cop car, never to be contacted again. In short, she had no idea what she was talking about. No idea that if my abusive ex parter who had a criminal record the length of my arm, who had plead guilty to putting my body through a wall, who openly admitted to calling me a disgusting slut, was found “not guilty” of rape, of course my respected professor parents and their socially acceptable incest would definitely not be found guilty in a court of law. There is no way to tell the story of incest in a way that will definitely be believed. It is not the act of incest that is forbidden; it is the telling of it that is.

This same “friend” then threatened to call 911 on me because I was experiencing thoughts of self-injury. The insistence that survivors stay silent about incest and the insistence that we are crazy and must be incarcerated go hand in hand.

I managed to survive last summer without being locked up and without walking back anything I’d said. I posted the email in which my mother threatened to sue me on my instagram (without naming her) and 3000 people liked it. She backed off with her threats (I played chicken with my mother and won). I compiled my writing on incest into a zine called The Realm of Unreality. I went to Barcelona and Toulouse and shared my writing with other survivors. I came back to Montreal and launched the zine here, and in preparation for the launch I wheatpasted excerpts from the zine on the walls of my city. The opposite of being silenced — I was letting my story spill out all over the walls. I was making incest something that could be said in public. I told myself I had won. I had refused to be silenced. I wasn’t silenced. But my goalposts had been shifted. I had wanted to name my mother and I had been made to defend my right to speak the truth without naming her. Since I had refused to walk the truth back, and that was already seen as so dangerous, I was supposed to be satisfied. It was supposed to be enough.

It took me another year to name her. In that time, I realized that I wanted and needed to name her. I knew that this impulse was not punitive and was not out of alignment with my principles. I knew that stating that my famous mother who is considered an “expert” on feminist mothering had repeatedly and knowingly brought my sister and I to our grandfather who was sexually abusing us, had allowed and enabled our father in enforcing our submission to our grandfather’s sexual abuse through his punishment, shaming, and rage, had severely neglected her children and offered us no help as we spiralled out of control from complex trauma, had literally rolled her eyes at me when I was seventeen and said “all grandfathers do that,” and had threatened to sue me, at 37, for writing about the fact that my father was demonstrating red flags for escalating his sexual abuse that caused me to need to move my little sister out of the house when I was a teenager — was necessary.

Child abuse is not like other forms of abuse, and it is definitely not like the recasting of conflict as abuse and personal vendettas dressed up as righteous justice that so often constitute cancellation campaigns. I believe that child sexual abuse and incest should be named publicly for the protection of children because children cannot protect themselves. Child sexual abuse prevention cannot depend solely on the naming of perpetrators because most perpetrators are never named, but naming perpetrators is an essential part of child sexual abuse protection, because care givers need to know who not to allow around their children. While I believe that everyone is capable of change and should not be defined solely through the worst things they’ve ever done, child abusers are notoriously sneaky, and therefore it is one strike you’re out. If you abuse children sexually or you allow children to be abused sexually you should never be allowed access to children again. And this goes for all forms of child sexual abuse, including “jokes,” “games,” sexual comments, forced kissing, or any other type of child sexual abuse that we collectively enable by dismissing it as “minor.” No type of sexual abuse against children is minor.

In my mother’s case it is especially necessary that she be named publicly because she is literally an “expert” that countless others defer to on the subject of “feminist mothering.” Her treatment of her children can neither be described as feminist or as mothering. My mother was an abused, neglected, and unmothered child who went on to repeat the cycle. Her career is an elaborate shield in which she justifies the neglect of her children by theorizing that what really matters in the mother-child dynamic is that the mother’s preferences be prioritized at all costs and that mothers never be “blamed” for neglecting or abusing their children.

After I finally wrestled my way through the brainwashing of my family and the larger culture, as well as the well meaning cautions of the people closest to me, and found the strength and courage to do what I needed to do, I was shocked by the anticlimactic outcome. I had protected my mother’s identity so carefully over the years because I was trying to prevent her from experiencing a scandal. Surely the fact that the founder of “motherhood studies” and one of the most internationally celebrated scholars of “feminist mothering” had threatened to sue her daughter for writing about the sexual abuse she experienced in her family would be a scandal. Right? After reposting my essay Monstrous Daughters and naming my mother, and even messaging a few of her colleagues directly I waited and waited and nothing happened. I looked at my mother’s facebook page over a week later and could tell she had no idea I’d even done this. I thought about Andrea Robin Skinner, who had publicly disclosed that her famous “feminist” mother, Alice Munro, had chosen to protect her daughter’s sexual abuser over supporting her daughter, long before her mother’s death, but the story did not get “picked up” until after her mother had died. After all that work of finding my courage and capacity to speak the truth, maybe it wouldn’t matter. Maybe things would go on, business as usual. My mother would continue to be cited as an expert in feminist mothering and the truth would be buried, because no one wants to talk about incest.

As more time passed, I started to become distressed. I sent off a few more messages to colleagues of my mother and received no replies. I started to lament to my partner, Jay, that nothing was going to happen, that my story would not be included when people engaged with my mother’s work. Jay asked me what I wanted and I quoted Andrea Robin Skinner: “I wanted this story, my story, to become part of the stories people tell about my mother. I never wanted to see another interview, biography or event that didn’t wrestle with the reality of what happened to me, and with the fact that my mother, confronted with the truth of what had happened, chose to stay with, and protect, my abuser.” Jay listened to me. Later that day they sent me a spreadsheet in which they had compiled the contact information for close to 100 of my mother’s collaborators.

I wrote the following email and sent it to every email on the list, along with a link to my essay Monstrous Daughters:

“I am writing to you because you are somehow affiliated with the field of Motherhood Studies and the work of my mother, Andrea O'Reilly, the founder of the field.

I have recently made the decision to publicly disclose that Andrea O'Reilly is my mother, as well as her role in the sexual abuse I experienced in my family during my childhood, and her repeated attempts to dismiss my trauma, pathologize me, and silence me, including threatening me with legal action last summer.

The reason that I am writing to you and others in the field of Motherhood Studies is because I believe that scholars and researchers within the field need to reckon with this reality. My mother's scholarship is heavily focused on concepts like "mother blame" but does not say anything about real maternal responsibility to meet children's developmental needs and protect them from violence, including sexual violence within the family. Her scholarship reads like an elaborate shield against responsibility for her own abuse of her daughters. Motherhood Studies, especially if it claims to be a feminist field, must concern itself with the rights and wellbeing of mothers, and also the rights and wellbeing of children.

I do not wish to punish my mother or to dehumanize her: violence is a cycle and my mother is also a survivor. I ask that engagement with this information come from a place of truly seeking to understand and end the cycle of violence, rather than punishing and scapegoating individual perpetrators. My mother's mothering wasn't all bad. The best of her mothering is what made me a writer, and it is in writing that I have found the courage to defy her and tell the truth of my experience.

Here is my story. I ask that you answer this call to responsibility by engaging with this truth and considering its implications for the field of Motherhood Studies.

Thank you for you time

Clementine Morrigan”

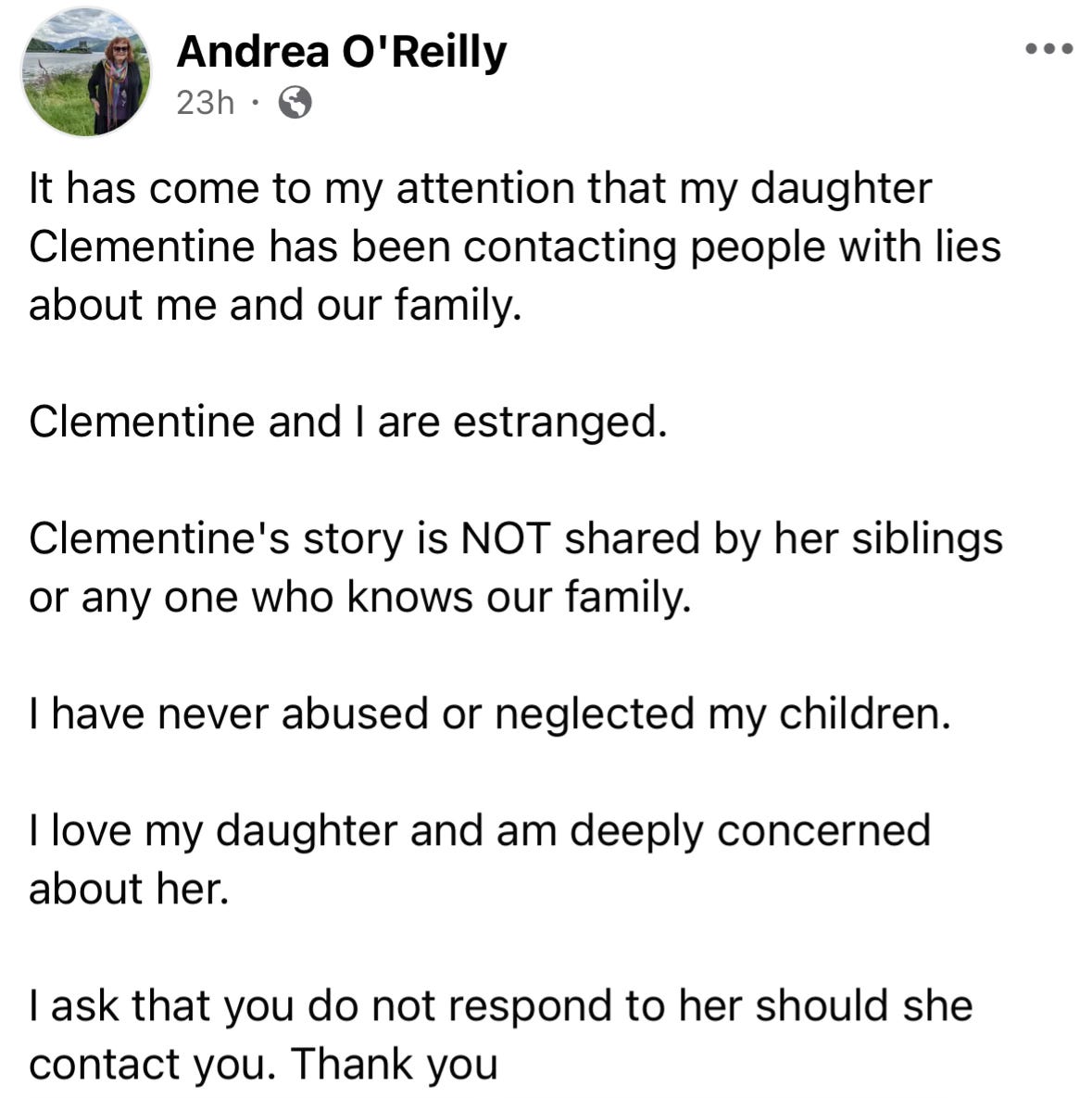

This email includes a clear call to action — I am asking that those working in the field of Motherhood Studies, who engage with my mother’s work, grapple with the implications of my disclosure. Although I sent this email to nearly 100 people working in the field of Motherhood Studies, it is now a month later and only 5 responded to me. Clearly, though, someone told my mother. By the next day she had posted this on her facebook.

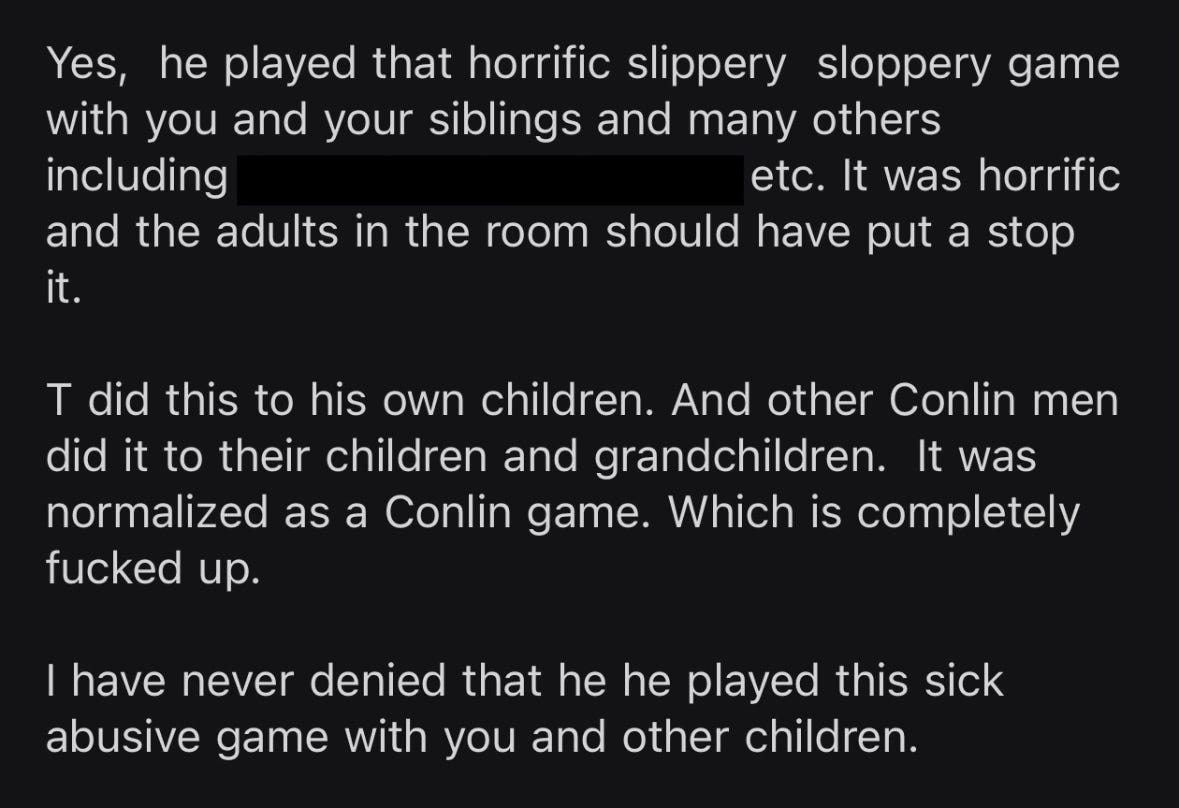

My mother admits that she took my sister and I to our grandfather over and over again throughout our entire childhoods, that she watched him forcibly licking our (and our cousins’) faces in a “game” our family called “slippery slobberies,” and that even after I told her he had put his tongue in my mouth when I was 12, I was still forced to see him until I was 15 and got the police involved. This is not disputed. It is established fact. And yet, publicly, she claims that she has “never abused or neglected” her children. She writes that she is “deeply concerned” about me which is a subtle way to imply that I am mentally ill, and she asks that people do not respond to me so that they cannot get any more information from me.

I watched as her comments filled with support, and as she deleted the few comments which expressed support for me. I remember one comment in particular in which someone who is clearly familiar with my work wrote something like: “What makes people believe that a writer who has written multiple books about incest has not in fact experienced it?” But my mother deleted that comment and any others that suggested maybe I really had been sexually abused. Despite my mother’s refusal to consider that my father is an incest perpetrator like my grandfather, she has, for many years, admitted to me that she knows my grandfather’s behaviour was “inappropriate” or even abusive, that him putting his tongue in my mouth when I was twelve was a sexual assault, and that she continued to make me see him after that, and yet in public, all of that disappears. The only thing that is left is the implication that I am crazy.

An excerpt from one of my mother’s emails where she admits to witnessing the abuse (I have blocked out the names of children). “T” here refers to my grandfather, Ted Conlin:

I am not crazy. I am also not the traumatized teenager, drunk out of my mind, breaking bottles and slashing my arms, screaming about incest, and being taken away with a police escort to the psych ward anymore. The very symptoms of surviving incest are used to discredit incest survivors. Someone behaving in ways we consider crazy and saying they were sexually abused in their family should be taken seriously precisely because “crazy behaviours” are literally evidence of child sexual abuse. But we collectively believe the delusion that “crazy behaviours” are caused by “chemical imbalances” (something that there is no evidence for) instead of trauma (something there is a huge amount of evidence for). I was not taken seriously as a screaming teenager because we live in a culture that collectively works to discipline and punish survivors. But I am not a screaming teenager anymore. I am a 38 year old professional writer. I have been stable and in recovery for close to 15 years. I run a successful business selling my writing, I have two secure long term partnerships, I pay my taxes, and I haven’t had a drink since 2012. My huge body of work is read and translated internationally and I am probably more famous than my famous mother. Yet she still tries to dismiss me as crazy.

Realizing that there would be no scandal and that most people would respond by ignoring me hit like a heavy blow. I realized I had spent decades protecting my mother from something that was never going to happen because most people want stories of incest to go away. I told myself that what matters is that I told the truth and I would continue to tell the truth, and that those who are ready to face this truth would find me and join me in breaking the spell of unreality.

I received endless dms and emails from survivors who were abused, neglected, and not protected by their mothers, including many whose abusive and neglectful mothers were successful, professional, and/or “feminist,” and many whose abusive and neglectful mothers were considered “experts” in their “feminist” or “healing” fields. I did a poll on my instagram in which the majority of people who were abused in their family of origins reported that their mothers focused on their own feelings and desire to be seen as a “good mother” when confronted with their children’s trauma. I wrote to Andrea Robin Skinner and shared my essay with her. She wrote back with the most affirming words. I felt us connected through our extremely similar stories and our shared courage as truth tellers and cycle breakers. I was contacted by Finnish writer, researcher, and activist, Koko Hubara, who is currently do a research project and writing a book in Finnish on the topic of “daughtering,” a feminism for daughters, in part in response to my mother’s work on “resisting daughter-centricity.” We will be in touch to discuss our complimentary work on the subject further. I started to allow this avalanche of support and shared commitment to truth telling to soften the blow of silence from those in the field of Motherhood Studies. I saw that I am not alone, and that together daughters are going to break our way into Motherhood Studies and force a reckoning.

Then I received an email from Alessandra Fraissinet, one of the hosts of an Italian podcast titled Ti leggiamo una femminista. With permission, I am sharing our email exchange here:

“Dear Clementine,

My name is Alessandra Fraissinet, a long-term follower and reader of your work, and I co-host an Italian feminist non-fiction podcast called Ti leggiamo una femminista, with my close friend and collaborator Annalisa Sirignano. We’ve been producing the podcast since 2020, and over the years it has grown a decent following and some recognition from publishers (although it remains self-funded and supported by small listener donations).

I’ve long been a reader of your zines and long-form writing on trauma, sexuality, polyamory, veganism, and cancel culture. I really appreciate your contribution to these topics, as well as your courage and commitment to be a truth-teller. Your work has had a meaningful impact on both Lisa and me, and we could not thank you enough for it.

This is where the difficult bit comes. Earlier this year, Prospero Publishing gifted us a copy of Maternità femministe, a curated collection of Andrea O’Reilly’s work translated into Italian by Veronica Frigeni.

At the time, you had not yet disclosed publicly that Andrea O’Reilly is your mother. While I suspected a connection due to her being Canadian and a world-wide known scholar of feminist motherhood, I was unable to find confirmation of this. Around the same time Lisa and I were discussing this, Veronica Frigeni reached out to us expressing interest in a collaboration. We eventually decided to move forward and feature the book, given that we had never previously covered motherhood as a feminist theme. We interviewed Veronica and released the episode in June 2025.

After discussing this at length, Lisa and I decided to address your story at the end of the interview. We centered our final question to Frigeni, who is also a mother, around the ways in which the professional success and recognition of many boomer women has often come at the cost of their daughters’ safety and wellbeing within patriarchal households, as you have articulated in your work. We specifically named you and mentioned your story because we could not ignore what we knew. We intentionally refrained from speaking about O’Reilly in overly celebratory terms although we did appreciate the ideas expressed in the book.

The episode ended up being one of our most listened-to and most appreciated by our audience.

When I read your Substack Monstrous Daughters and learned that Andrea O’Reilly is indeed your mother, my heart dropped. Lisa and I have since spoken at length about the ethics and implications of having platformed the book, and have been trying to come up with the best way forward. I hope you will believe me when I say that our decision was not made with any malicious intent.

We want to be transparent and take responsibility, since many of our listeners became familiar with your work, as well as with O’Reilly’s book through us. In November, we intend to release a follow-up episode where we:

- explain the context of how we came to cover Maternità femministe;

- state clearly that we believe you;

- reflect on the complexities of consuming the work of authors who have caused harm;

- encourage our listeners to make their own informed choices about engaging with O’Reilly’s work;

- affirm that rejecting her work entirely is a valid response.

Because this directly concerns you, we wanted to reach out before releasing this episode. We’d like to give you the option of adding a statement or comment, should you wish. There’s of course no obligation, we simply want to make sure you’re aware and that the space is open to you if you want to use it. We fully understand that you may not be interested and are ready to face any response.

Thank you for reading this, and for the work you continue to share. We hope this approach feels thoughtful rather than intrusive, and we welcome any guidance from you.

With respect and solidarity,

Ti Leggiamo una Femminista

Podcast transfemminista intersezionale”

“First, I want to thank you deeply for the thoughtfulness of this email, and for the thoughtfulness you describe throughout the whole process, even before you knew for sure that she is my mother. You are answering the call that I have put forth, and did so even when you didn't know that she was my mother, because that call is still relevant for any feminist scholar working on motherhood. The voices and experiences of daughters, and children generally, matter, especially those who have been sexually abused in the family. It matters a lot to me that you are treating me not just as a victim, but as a political thinker in my own right who is bringing something important to the work of feminism. So truly — thank you.

I also really appreciate that you are doing a follow up episode to clarify the connection between my mother and I. And I appreciate you asking for my input. What I would like you to highlight is that child neglect is actually present throughout my mother's work. It's not that she has advocated for truly feminist mothering that meets children's needs and protects children while also allowing mother's their personhood and self outside the role of mothers — and that her personal life did not live up to that vision. In fact, she says almost nothing about children except to mock and dismiss children's needs, and to express nostalgia for a time when it was more socially acceptable to neglect your children.

Here is just one example where she states that in some ways 1950s motherhood was better for mothers because it was more acceptable to be a "bad mother":

I think a lot of well meaning feminists assume that she can't really be serious when she says things like this, and that she really only wants a situation in which the entire work of mothering does not fall on mothers alone. In fact, she really is advocating for child neglect as the solution to the problem of how mothers can have children and still have lives of their own. That is both what she consistently describes in her work, and also what she did in her life.

To me this is a much bigger problem than whether or not people engage with her work after learning that she neglected and abused her children. I think simply opting out of her work is stepping away from the bigger questions. Some bigger questions I would like people to grapple with are: How is it that so many feminists do not seem to notice that she is openly advocating for child neglect? How is it that so many feminists see no issue with a "feminism for mothers" that says nothing about the actual work of mothering (meeting children's needs, protecting children)? Why are children's rights put in opposition to mother's rights and why does no one seem to have a problem with this framing? And finally, if child neglect cannot be the solution to the dilemma that mothers face — what is the actual solution? How can mothers be deeply and robustly supported, allowed space for their personhood, outside interests, and careers, while children's developmental needs are met and their safety and dignity are protected? These are the questions I would like scholars of feminist motherhood (and everyone else) to grapple with.

It is also important to me that the specific dynamic of daughters being offered up as sacrifices in patriarchal families so that mothers can have their freedom and careers be named. I am really grateful that you brought that up in the original interview. I see this dynamic in the case of Alice Munro and her daughter Andrea Robin Skinner. And I have received many dms and emails from incest survivors who have successful, professional, "feminist" moms who did not protect them and in fact demanded their silence. I have written more on this dynamic here:

https://www.clementinemorrigan.com/p/we-need-a-feminism-for-daughters

and here:

https://www.clementinemorrigan.com/p/what-if-your-mom-is-a-famous-feminist

I don't know if it's possible, but if there is a way that you could send me a transcript of the final question in the interview where you asked Veronica Frigeni about this dynamic, I would love to translate it. I am very curious and eager to hear this talked about and curious about her response. Frigeni is the co-editor on my mother's proposed book about "resisting daughter-centricity” which was the final straw for me in deciding to publicly name my mother. Frigeni is one of the first people I messaged to disclose my mother's identity and I have been left on "read" without a response.

I was also wondering if you would be okay with me publishing this exchange on my substack. I sent my article to almost 100 of my mother's colleagues, asking explicitly that they consider the implications of this information in their scholarship on feminist mothering. I received a response from 5 people. Your email and the process it describes model perfectly the sincere engagement I am asking for and I think it would be generative to share it as a model for what it means to not turn away from this conversation.

Thank you again. Your response means everything to me.

Clementine”

“Dear Clementine,

We’re so glad our message came across as intended rather than intrusive or inappropriate.

We’ve taken note of your reflections and questions, and we’ll be sure to include them in our November episode. We also wanted to ask if you might be interested in joining us as a guest speaker on the podcast. Only if this feels right for you and if you think it would contribute meaningfully to the conversation, absolutely no pressure. The only challenge on our end would be accessibility, since a large part of our audience doesn’t speak or understand English.

Please feel free to post our email exchange on Substack if you'd like to do so.

I’ve attached a transcript and translation of our final question to Frigeni. I’ve already translated it for you, but of course feel free to double-check it. For transparency, we’ll also be emailing Frigeni to let her know we’re releasing a follow-up episode.

Thank you again,

Ti Leggiamo una Femminista

Podcast transfemminista intersezionale”

“Thank you so much for the thoughtful response and the transcript / translation.

I’d be happy to come on. Maybe we could just do a very short segment as part of the episode, that way you could translate it and have it repeated in Italian rather easily. Let me know your thoughts.

I’m travelling a fair amount over the next couple months but I am sure we can find a time to record something.

Thanks again for your principled integrity on this. It really means the world to me.

I will post the exchange and a reflection on my substack some time soon.

Thanks again.

Clementine”

Here is the translated question and answer which was asked and answered on the podcast episode about my mother’s book:

“Ti Leggiamo una Femminista: So, we’ve come to our final question, which is less of a question and more of a reflection: while reading this book, we couldn’t help but think about the experience of women like Clementine Morrigan. For those who don’t know, Morrigan is a Canadian writer and activist who has often spoken in her work about the sexual violence she suffered from her paternal grandfather as a child, and about how her mother, a prominent academic in the field of motherhood studies, ultimately failed to protect her from this abuse. We should also note that Morrigan used a pseudonym precisely to preserve her parents’ reputation, as they are both professors and prominent academics who, nevertheless, were complicit in the abuse. In an Instagram post, Morrigan also spoke about how many boomer-generation mothers, like her own, achieved professional success often at the expense of their daughters, choosing not to challenge the patriarchal abuse within their families. We’d like to ask what you think about this, and if you could expand on the difference between emancipated motherhood and feminist motherhood.

Veronica Frigeni: Thank you very much. This is an extraordinarily powerful question precisely because it is also radically unsettling. I think it ties back to why I first became interested in feminist thought on motherhood, which eventually culminated in translating Andrea’s work. I became a mother in 2014, the same year the book on neoliberal feminism was published. That was a historical moment in which the dominant voice within feminism was neoliberal feminism, the idea that you can “have it all,” which we know very well is complicit in upholding structures of privilege and marginalisation within patriarchy. Your question highlights what I see as a blind spot in many progressive narratives on motherhood: the gap between personal, individual emancipation, which is often hierarchical and competitive, and feminist motherhood. Personal emancipation can be a positive first step if it leads toward relational, collective liberation, but all too often, as we have seen, it remains paralysed in complicity with patriarchy, reproducing its very logics of power. Some mothers may have broken the glass ceiling, but who is left to pick up the pieces? In the Italian context, this can be compared to maternalism, an ideology that rewards women for being “naturally” suited to motherhood, assigning them the civic role of society’s moral guides. This is nothing more than another sugar-coated version of patriarchy, a symbolic compensation that keeps its logic intact. Feminist motherhood, on the other hand, is something entirely different: it is a constant assumption of responsibility, political and relational, that is born and nourished within relationships; it stems from feminist consciousness and is therefore inevitably collective. It is an ongoing practice of responsibility, listening, and breaking with complicity, one that interrogates all forms of marginalisation. To put it simply: feminist thought on motherhood, matricentric thought on motherhood, is inevitably transfeminist [meaning cross-feminist — not used here in the sense of a feminism that centres trans women, or trans people, but that would be included in this definition]. This is where we see a considerable distance from the theories of the symbolic order of the mother that shaped a certain strand of Italian feminism. In short, and I’ll conclude here, feminism must start again by asking how motherhood can be transformed, making it not only a site of rupture with patriarchy but also a space of real, concrete alliance with anyone who suffers its oppression and its wounds.”

Despite Frigeni’s thoughtful response to my challenge when applied to my mother’s work in the hypothetical, she has not responded to me or in any way addressed the fact that my mother’s work, which she translates and promotes, is far from being what she describes as “a constant assumption of responsibility, political and relational, that is born and nourished within relationships; [that] stems from feminist consciousness and is therefore inevitably collective…. [that] is an ongoing practice of responsibility, listening, and breaking with complicity, one that interrogates all forms of marginalisation.” My mother’s “feminism” as well as her “mothering,” refuses responsibility, actively works to silence her abused daughter, and upholds complicity with patriarchy, incest, and child sexual abuse. This is not a personal or private matter. It is explicitly political. Because of my mother’s position as an “expert” in the field of Motherhood Studies, it is a necessity that feminist scholars within this field take up my challenge and call to action. I am hoping that Frigeni and others working in the field of Motherhood Studies will take seriously my call to grapple with the implications of my story to my mother’s work. As Friegi herself says, “feminism must start again by asking how motherhood can be transformed, making it not only a site of rupture with patriarchy but also a space of real, concrete alliance with anyone who suffers its oppression and its wounds.” I am one of those who has suffered the oppression and wounds of patriarchy, as a direct result of the choices of my “feminist” mother whose work she promotes. I am asking for solidarity.

I am deeply moved by Alessandra Fraissinet’s answer to that call. Even though she was not one of the close to 100 people who I directly asked to engage with the implications of my disclosure, she immediately did what I asked. Even before she knew for sure that Andrea O’Reilly is my mother, she still felt that it was necessary to include my analysis that daughters often bare the cost of professional “feminist” mothers’ freedom by absorbing the shock of patriarchal violence within the family, when discussing a book on “feminist mothering.” As soon as she realized that Andrea O’Reilly is, in fact, my mother, she decided to go further by explicitly naming this fact and giving space for me to directly express my opinions on my mother’s work.

For all those who feel unsure how to proceed with responsibility in the face of this information — I share this email exchange as a model. This is how.

Clementine Morrigan is an underground writer, cultural change maker, moral philosopher, and brazen truth teller. She is the author of numerous zines and books, including the cult classic zine Love Without Emergency, which will be released as a book with Microcosm Press in 2026. Her popular zine series Fucking Magic was released as a book with Revolutionaries Press in 2025. She co-hosts the podcast Fucking Cancelled with Jay Lesoleil. Her work is known for its unflinching engagement with taboo and difficult topics. She works for a world where the dignity of all beings is recognized and protected.

F*cking Magic is a collection of 12 zines originally hand-made by Clementine Morrigan and posted throughout the world. From alcoholism to sobriety, surviving incest to BDSM, throughout the seasons and many iterations of becoming, Morrigan leans into the darkest and most vulnerable parts of her life in this cult coming-of-age memoir that speaks to taboos and universal truths. You can order it here.

I am excited to announce that I will be a contributor to an important new anthology titled Depsychiatrization, calling for the abolition of psychiatry. “We’re breaking new ground in formulating the immense potential in disregarding psychiatric pathologization entirely. Improving psychiatry is not enough. We need change.” Stay tuned for more info as the project unfolds.

Kudos to the Italian podcaster, and to you for speaking up. How refreshing to see someone responding the right way to your disclosures.

I just signed up for a paid subscription, despite being a broke and unemployed artist, because I wanted to leave a comment of support and solidarity.

I want you to know how important your work has been to my communities here in Melbourne, Australia, the fact that you always ground your work in your principles, empathy and bravery has helped me to form stronger interpersonal and community bonds. In times of black and white thinking, I deeply admire how you do not shy away from complexity and this informs my own art practice and is helping me slowly find my way back to my own voice.

I have watched you sharing your story about this and it has generated many long conversations between myself and my loved ones. Your story has helped me to better understand the experiences of childhood sexual violence of someone very close to me and for that I am deeply grateful.

Recently, I was reading about Gisèle Pelicot's daughter, who is currently estranged from Gisele because despite Gisele standing up bravely against the horrific sexual violence perpetuated on her by her husband, Gisele was unable to accept that her husband had also done this to her daughter. I found reading about their story heartbreaking and devastating, I wondered if Giselle's trauma was simply too much for her to face the horrifying truth of her daughter also being a victim, or is she couldn't face the shame of not being able to protect her because the pressure on women is so immense. In any case, it made me feel so goddamn sad. My heart absolutely broke when I read her daughter's words of immense hurt that though she had supported her mother through the court cases, her mother was unable to do the same for her. I thought of you and I thought of all the similar stories I've heard from women across my lifetime. What a wound it must be to not only be hurt by gendered and incestuous sexual violence... but to not have your mother, a public figure, stand by your side...

How utterly, devastatingly heart-breaking. But I believe that people sharing their stories can be a way of shining light into the dark and I believe that is what you are doing by sharing your story. Thank you for breaking the silence. Thank you for your commitment to using your powerful and clear adult voice to speak for those who are most vulnerable and often voiceless - children and animals. Thank you for asking us to face our complex, messy humanity because only by not shying away from the complex and uncomfortable can we find ways to break these generational, cultural and institutional cycles of violence.

You have my deepest respect.