Monstrous daughters

On feminist mothers, scapegoats, and the inherent dignity of little girls

Dedicated to Kelsey Zazanis, for making me brave.

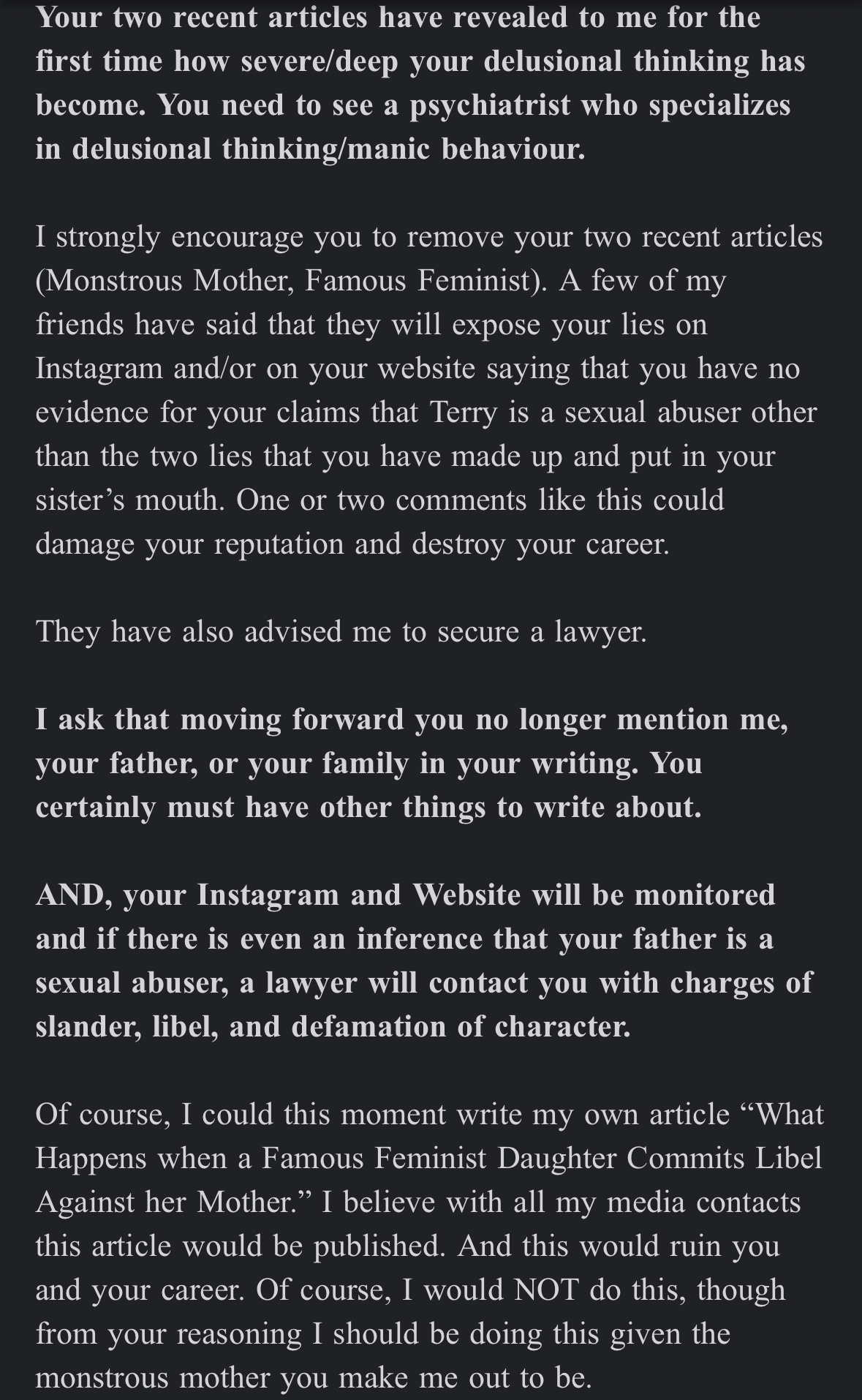

I wrote this article almost exactly a year ago. At the time, I was writing for the first time about the fact that my mother is a famous feminist scholar who works in the field of feminist motherhood. Not only did my mother not protect me from the sexually abusive men in my family, but she demands my silence on the subject of her identity and role in the abuse, and on the sexually abusive behaviours of my father. After writing this and a few other essays on the subject, my mother sent me many harassing emails calling me delusional and a liar, and threatened to sue me if I continued to write about the sexual abuse.

At the time, everyone in my life panicked about her threat and encouraged me to “be careful.” I decided to ignore their advice and I shared the above excerpt from her emails on my instagram while blocking out my father’s name and not naming her. I was advised that I should take it down but it felt extremely wrong to take it down so I didn’t. After seeing that I had done that, she backed off with her threats and left me alone.

I have been trying to get pregnant and hoping to become a mother. As I searched for resources on empowered, feminist mothering I found my mother cited and quoted over and over again. The same woman who treated me with such neglect and continues to treat me with such cruelty, who allowed her daughters to be sexually abused their entire childhoods, and who threatened me with legal action for telling my story while still protecting her identity, is the expert who so many defer to when discussing feminist mothering. It makes my head fucking spin.

I changed my name early in my writing career to protect her identity. I did not even mention the fact that she’s a scholar of feminist motherhood in my writing until last year when I was 37 years old. I have always deeply loved and empathized with my mother. I have always wanted to be able to have a relationship with her. I know that she is a survivor herself and she is extremely traumatized. I have a lot of compassion for her. And, I think it is wrong that a woman who abused her children by repeatedly bringing them to a sexual abuser, and who continues to demand my silence on the sexual abuse in our family, is held up as a world renowned expert on feminist mothering.

Like many incest survivors I grappled endlessly with the ethics of publicly naming my perpetrators. Those who are familiar with my work opposing cancel culture and prisons know that I oppose the dehumanization of perpetrators. I do not want my mother or my father to be dehumanized. I do not want them to be punished. I know that this is the typical way the public responds to disclosures of abuse (when the survivor is believed): by dehumanizing and punishing the perpetrators. My work has always asked for more from people. My work has always asked that we hold the reality of abuse and the humanity of perpetrators together at the same time. Failure to do so is to turn our backs on our responsibility to face and transform the cycle of violence.

Eventually I realized that I needed to tell the truth about who my mother is and that I am not responsible if people respond to the truth by dehumanizing her. I have done everything in my power to change the culture so that disclosures of abuse do not result in further abuse and dehumanization. I have done more work to humanize and offer compassion to perpetrators than any survivor I know, at great personal consequence to myself. I do that work because it is a necessary part of finally ending the cycle of violence. Telling the truth is also a necessary part of the work of ending the cycle of violence. Because my mother is a world renowned “expert” on “feminist mothering” I need to tell the truth in public.

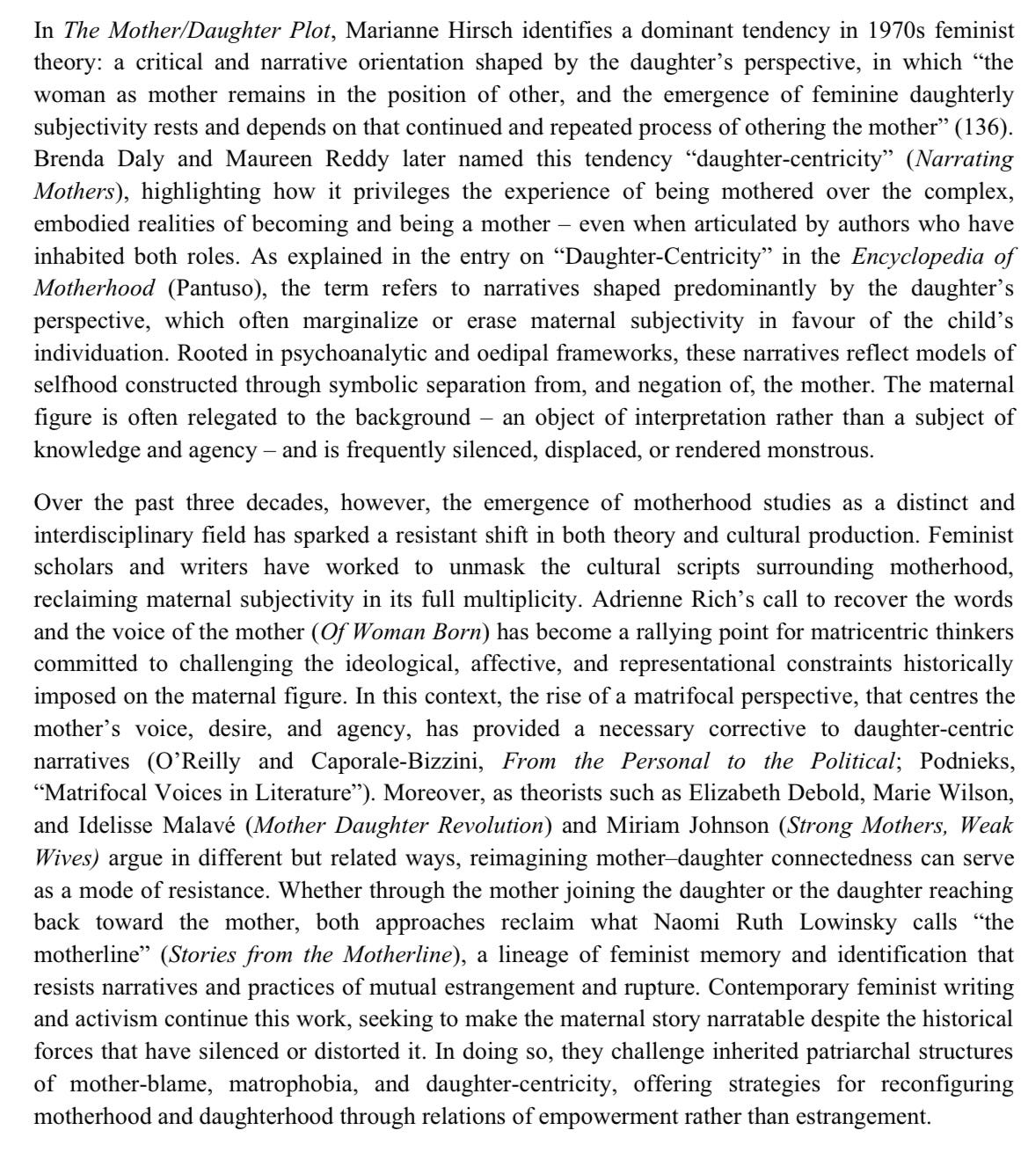

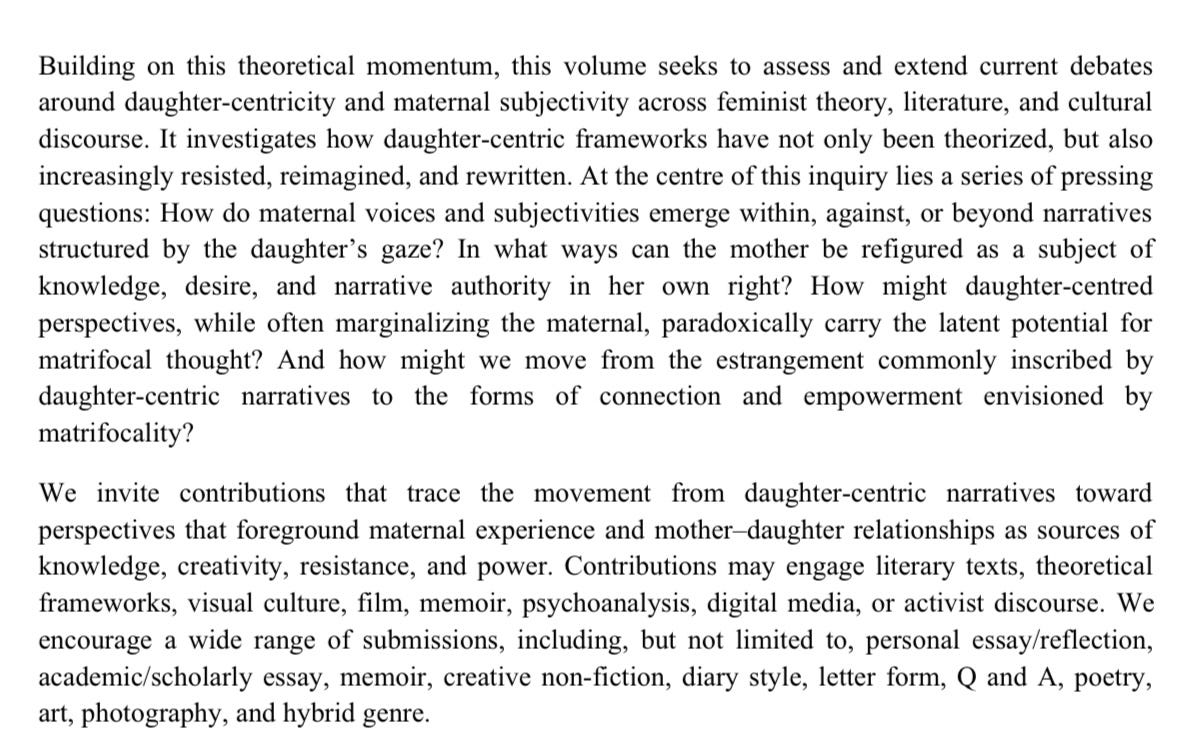

Recently I came across a call for papers for a new book my mother is co-editing on the subject of “resisting daughter-centricity, reclaiming matrifocality.” Here it is.

I don’t even have the words for how this makes me feel. Angry does not cover it. Unloved doesn’t either. My mother created this call for papers about “resisting daughter-centricity, reclaiming matrifocality” one year after threatening to sue me for writing about the sexual abuse in our family. This is the “daughter-centricity” that she is resisting — through threats of legal action. When I read this, something broke inside me. The long held hope that if I just found the right way to say it, that if I just approached her correctly, that if I just understood her enough, she would finally be able to hear me disappeared. I saw that her self-justification runs so extremely deep. I saw that she has no empathy or compassion for me at all. Despite being the woman who brought me into this world, her treatment of me cannot accurately be described as “mothering.” It certainly can’t be described as feminist.

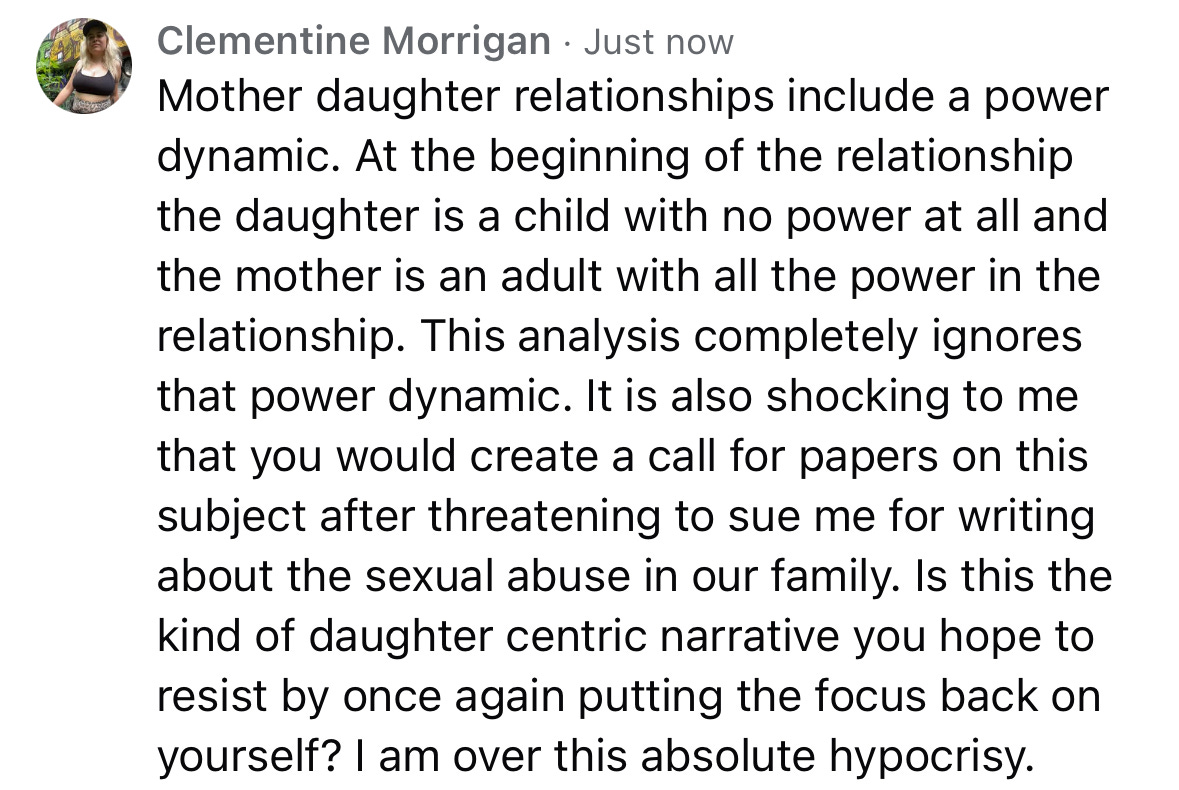

I commented below the call for papers, for the first time daring to say the truth publicly in connection with her name.

I felt a rush of power seeing those words there. Not punitive or dominating power. The power of truth telling. The power of meeting her denial and coercive silencing with the truth. Within minutes my mother deleted the comment and then blocked me on facebook. Once again she silenced me. Of course she did. But now something had opened up in me. Something had shifted. I knew that this book using academic mumbojumbo to justify her silencing her daughter’s speech on incest needed to be challenged. So I wrote to the co-editor of the anthology and told her the truth.

I always expected I would feel overwhelming guilt if I did something like that. I had felt overwhelming guilt for years even thinking about it. That was not my experience. Instead I felt a surge of power and energy, as if in silencing myself I had been holding down not just the truth but my life force. It felt good. It felt right. It felt necessary. I realized that there is no way for me to be well, to heal from my autoimmunity, to become a mother, or to recover from my trauma while I allow my mother to silence me. I am telling the truth.

My mother’s name is Andrea O’Reilly. Here is her official bio: “Dr. Andrea O’Reilly is internationally recognized as the founder of Motherhood Studies (2006) and its subfield Maternal Theory (2007), and creator of Matricentric Feminism, a feminism for and about mothers (2016) and Matricritics, a literary theory and practice for a reading of mother-focused texts (2021). She is full professor in the School of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at York University, founder/editor-in-chief of the Journal of the Motherhood Initiative and publisher of Demeter Press. She is co-editor/editor of thirty plus books on many motherhood topics including: Maternal Theory, Feminist Mothering, Young Mothers, Monstrous Mothers, Maternal Regret, Normative Motherhood, Mothers and Sons, Mothers and Daughters, Maternal Texts. She is author of three monographs including most recently Matricentric Feminism: Theory Activism, Practice, the 2nd Edition (2021). In spring 2024 a collection of her essays, In (M)otherwords; Writings on Mothering and Motherhood, 2009-2024, was published and in fall 2024 her next edited book, The Mother Wave: Theorizing, Enacting, and Representing Matricentric Feminism will be published. She is currently completing her monograph Matricritics as Literary Theory and Criticism: Reading the Maternal in Post-2010 Women’s Narratives. She is twice the recipient of York University’s “Professor of the Year Award” for teaching excellence and is the 2019 recipient of the Status of Women and Equity Award of Distinction from OCUFA (Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations). She has received more than 1.5 million dollars in funding for her research projects including her current one on Millennial Mothers.”

My father’s name is Terry Conlin. He isn’t famous. But that is his name. My grandfather is dead but his name was Ted Conlin.

To quote Andrea Robin Skinner, the daughter of Alice Monro, another famous feminist who did not protect her daughter from childhood sexual abuse: “I wanted this story, my story, to become part of the stories people tell about my mother. I never wanted to see another interview, biography or event that didn’t wrestle with the reality of what happened to me, and with the fact that my mother, confronted with the truth of what had happened, chose to stay with, and protect, my abuser.” I am not asking anyone to abandon my mother’s work or what it means to them. What I am asking is that this story, my story, be included in the discussion of that work.

This is my story.

My mother is a feminist and I grew up knowing about the concept of “mother blame.” My mother explained that mothers are held up to impossibly high and often contradictory standards, are not supported by the larger culture in the thankless work of mothering, and are likely to be blamed whenever anything goes wrong. My mother would point out mother blame when she saw it in the movies we watched. I knew about the trope of the “bad mother,” the “monstrous mother,” and how these tropes contribute to our collective dehumanization of mothers and our willingness to offer them up as scapegoats whenever anything goes wrong.

When I was a little girl I was sexually abused. It took me so long to be able to say that and not feel like I was lying, because in my family, our grandfather leering at the children, grabbing us and licking our faces, telling us he wanted to “neck with us,” telling us he would “steal kisses” from us in our sleep, and, finally, forcibly making out with me when I was twelve, was not considered sexual abuse. It was normal, standard behaviour that took place with many other adults in the room, including my feminist mother. When the children resisted our grandfather’s constant advances, we were punished. Our father would scream at us, something he did often, and call us selfish and ungrateful. It was ground into us that we needed to show respect to our grandfather, and according to our father, showing respect meant submitting to his advances without complaint. So, eventually, that’s exactly what I did. The day my grandfather finally escalated into forcibly making out with me, I walked into his arms willingly, despite everything in me screaming danger, because I was thinking about what my father had taught me, and I wanted to be good.

I remember my sister crying about my grandfather. She was even more vocal in her dislike of his advances than I was, perhaps because she was clearly his favourite. I remember her crying and I remember my mother telling her not to. My mother’s methods weren’t usually the outbursts of rage that my father preferred, they were more subtle. But she worked, alongside my father, to ensure that my sister and I would learn to be quiet and accept our grandfather’s behaviour. When I told her, in tears and panic, that he had cornered me in the bathroom and “put his tongue in my mouth,” she cried too and so did my sister. My mother told me it was good I told her and then nothing changed.

When I was fifteen and cutting myself, I was forced to see the school guidance counsellor which eventually led to her calling Children’s Aid and me being taken to the police station where they asked me about my grandfather in a little mirrored room. I told them about him, and then they drove me home in a cop car and dropped me off. My mother went in to talk to them. I remember her being emotional and hysterical. She told me that they told her “it’s not inappropriate, it’s abuse.” She made the decision then that my sister and I would no longer have to see him. My father and brother continued to go visit the extended family and they simply pretended that my sister and I had ceased to exist.

I thought maybe the police intervention would finally rouse some empathy in my mother. But that summer, the summer I was fifteen, I was constantly screamed at. By my father and by my mother too. I remember her bursting into my bedroom with a vacuum cleaner while I was sleeping, screaming at me for not doing enough around the house. I called my older boyfriend and told him to come get me with his dad’s car and he did and I ran into the driveway while my parents screamed at me, and I got into his car and I left. It didn’t matter that this older boy was sexually assaulting me. All that mattered is that he offered a way out.

My mental health continued to plummet: cutting, suicide attempts, skipping class constantly, having break downs at school, and then one day taking a glass bottle out of the recycling at school, smashing it, and carrying the shards into the town where I was found wildly slashing at my arms by the side of the road. I was locked up for that. My first time in lock up. And when I got out I was even more traumatized and even more crazy.

My parents showed no empathy. They were mad at me. In fact the first time my father noticed the cuts on my arms his first words were “How could you do this to your mother?” My feminist mother, who is literally a scholar of feminist motherhood, never talked to me about the sexual abuse, beyond defending herself against my accusations. She insisted she never knew that I was “so affected” by my grandfather making out with me, but her tone was one of exasperation and anger, not empathy or regret. She was angry at me. Angry at me for telling. Angry at me for being so crazy and so bad. Angry at me for refusing to comply with the family narrative that nothing out of the ordinary had happened. Sometimes I felt like she hated me.

I moved out at sixteen and spent two years living on my own in Toronto. My mother paid my rent and gave me money for groceries but she never had any idea where I was. Whenever we visited it would end in a screaming match, me insisting that I was abused, her rolling her eyes and telling me “All grandfathers do that.” I dropped out of school after school, started drinking and getting high all the time, and continued cutting myself regularly and trying to kill myself from time to time. My mother got the phone call that I was in lock up again for trying to kill myself. She came. But she always seemed angry at me and exasperated. The love I was so desperately seeking was not available to me.

When I was 17 I got wasted out of my mind at a giant party at my parents house. I chugged a 26er of liquor straight and went completely insane. I was, as I usually was when drunk, screaming about incest. I also smashed a bottle and started cutting myself. I was taken with a police escort in the ambulance to the psych ward where I was locked up again. I remember standing between my father and the cop, pointing at my father and screaming that he was a fucking pedophile. In the psych ward there was no discussion of incest or abuse. They tried to medicate me while I was still drunk but I refused. They told me I have a drinking problem. This episode did not convince my mother that maybe I had in fact been seriously traumatized. I went back to the city.

When I was 18 I moved back home for one year as a last ditch effort to try to finish high school because things were spiralling out of control in the city. When I moved back I was a full blown alcoholic who was drunk and/or high literally all of the time. Me and my 16 year old sister started drinking to black out together constantly. It became a ritual of truth telling. When we were drunk out of our minds we could say it. We could talk about our grandfather and the terror of being a child who knows that an adult in the family wants to fuck you and none of the adults who supposedly love you protect you. My sister and I were so visibly crazy. Our parents would yell at us about it but they would also supply us with endless access to alcohol.

During this time I was working a job at the mall and saving money to get the fuck out. I knew I needed to get away from my parents, so I was making a plan to get far away. Then one night in one of our binge drinking sessions, my sister broke down sobbing and told me that I could not leave her when I left. She told me that when I was living in the city, our father had started coming downstairs and standing outside her bedroom at night, during times when our mother was away travelling. She told me he had given her a secret gift and told her she was his favourite. We both knew what it meant. We both knew the horrible suspicion that had always been there. My sister begged me to take her out of that house, away from my father, and I did.

For six years my sister and I lived together. We lived in poverty and addiction and had experiences that few of our class background will ever have. The daughters of professors, our lives consisted of constant drunkenness, constant physical and sexual violence from men we knew and men we didn’t, insane crazy break downs in public, crack around us all the time, boyfriends who were in and out of jail, cockroach infested apartments, cheese sandwiches from the Sally van, panhandling, prostitution, you know — just incest survivor things. My mother knew about all of this. We sometimes called her wasted in the middle of a fist fight. She saw our apartments and the way we lived. And she never tried to intervene. She never even had a talk with us about it not being normal. In fact, she would give us gift cards to the liquor store for Christmas.

My mother was teaching at a university, writing and publishing books, travelling the world, speaking on panels, and being interviewed as an expert on feminist mothering, while her daughters were hanging out with homeless people and experiencing repetitive concussions. If she noticed the dissonance she never said anything. My sister and I did not realize how completely off the deep end we had gone, how insanely abnormal our lives were, because our mother, who is normal and well respected and feminist, made no comment on it. Her non-reaction affirmed for us that this must be normal. Just like in our childhood, she made no move to protect us, so we did not think we deserved protecting.

I pulled myself out of this darkness on my own by finding free therapy and going to AA. It never occurred to me once (in fact it just occurred to me now) that maybe my tenured professor mother could have paid for therapy for me. But that was never offered and I never even thought to ask, so I got by on what I could find for free. I saved my life through an insane amount of audacity, tenacity, and stubborn grit. I worked my ass off and got myself into a normal life. Over the years I had varying degrees of contact with my mother, sometimes trying to have a relationship, sometimes having almost no contact, and then, eventually, going fully no contact.

When I was 30 I gave my parents an ultimatum: go to therapy or I won’t have any relationship at all with you. It was too painful and too dangerous for me to maintain the dissociation required in order to be in relationship with them. I needed them to come into reality. I could not keep joining them in the realm of unreality. My father said no. My mother, eventually, went. At two years of therapy she started emailing me and telling me she was ready for a relationship. I told her that I didn’t think she was. I’d been in therapy for ten years or so at that point and did not believe my mom was ready to come into reality after only two years of therapy. But she kept pushing so I said fine. I was mad at her for pushing my boundaries and certain she was not ready to come into reality but I snapped and I told her.

I told her what an unsupportive mother she had been. How alone I had felt. How crazy it was that she didn’t protect us. I told her, for the first time, what my sister had told me all those years ago when I was 19. This horrible secret about my father that I had carried for 15 years. Her reply was immediate. She called me delusional. She said my partner is abusing me and planting stories in my mind to separate me from my “loving family.” She flat out denied the possibility that I could be telling the truth. She said she had never heard such “anti-feminist and mother-blaming rhetoric” in her life. She also went from respectfully they/theming my partner to suddenly he/himing them, and made some kind of jab at my polyamory calling me “polygamous.” In that moment, I went no contact.

Over the next couple years my mother would send me occasional emails telling me she loved me and missed me and begging me to find a way to forgive her for not doing enough when my grandfather forcibly made out with me when I was twelve. She has never once acknowledged what I told her about my father or how she reacted. She just acts as if it never happened, and I’m sure she is dissociating heavily about it. When I was 35, I took part in ayahuasca ceremony, and came to the decision to offer my parents grace. I visited them a couple times, entering into the realm of unreality briefly, never mentioning the unspeakable things.

I love my mother. I have always had deep empathy for her. I have always understood that her inability to protect me stems from the fact that she was not protected. I have spent countless hours thinking about her trauma and her pain. I understand her and I love her and I don’t even blame her for her failures because I know that her childhood was even more fucked up than mine. I have always protected my mother: changing my name so that I could write about my life without causing a scandal for her, keeping identifying details out of my writing. I never wrote about the fact that my mother is a scholar of feminist motherhood. I never wrote about what my sister said about my father, and what I know to be true about my father, in anything other than vague, cloaked language. I never wrote about the cruelty and contempt my mother has treated me with. And I never wrote about how insanely painful it was to have her react that way when I told her.

I thought I made peace with the situation. I had created so much healing for myself and I know my parents are very sick. I thought I could enter the realm of unreality and give them the love I want to give them, while trying not to get my inner child’s hopes up that they might be able to show me real love back. I know they refuse to be in reality and so I met them where they are, even though that was insanely hard. I did it because I needed to, and I hoped to be able to keep making little trips into the realm of unreality to give my parents love.

Then I decided to become a mom, and when my partner and I started trying to get pregnant, I went fucking crazy. My trauma and structural dissociation came up heavily. My terror at somehow not protecting my child made me hyper-vigilant. I knew I could never let my father see my child and I feared another cruel attack from my mother when I eventually had to tell her this. I could feel myself coming apart from the impossibility of holding both reality and unreality. I could feel myself coming apart as I tried to mother my mother while I knew she was never going to mother me.

I had to write and so I did. In a frenzy I started writing about incest. It felt necessary to get the truth down and to say it in public. It felt necessary to take a stand in reality, to plant my feet firmly on the ground and say “This is what happened” no matter what we were all pretending when I went to visit my parents. And in this writing, without much thought, I found myself breaking the rules I had always set for myself. I found myself writing about the things I had never let myself write about. I found myself telling the truth. It felt terrifying and exhilarating and crazy. I didn’t know how to reply to my mother’s texts. I didn’t know how to keep playing along in the realm of unreality. I started smoking weed. My partner and I took a break from trying to get pregnant so I could smoke weed all day and process my trauma. And I wrote.

Months of weed and writing and therapy and talking about it with the people I love. I felt insane and completely split down the middle. Reality and unreality pulling at me. Insane guilt for risking outing my mom. Tremendous certainty that if I did not tell the truth I would be putting my future child at risk. Holding the impossible things side by side and feeling unable to integrate it. Dry retching and sobbing and talking about incest. Thinking about incest. Writing about incest. I know my mother follows me on Instagram now and as I posted article after article about incest I wondered if at some point it would be enough to break through her denial. I feared another attack but so far she simply ignores it and continues to text me unreality texts.

Then Andrea Robin Skinner wrote an article about her famous feminist mom, Alice Munro, who did not protect her from childhood sexual abuse and took the side of her perpetrator. The parallels with my own story are striking. For the first time in my life I heard someone else describe the experience of their feminist mom using feminism to deflect responsibility for not protecting her daughters from sexual abuse. I heard another mother selfishly centring her own feelings while her daughter desperately sought what every daughter seeks: her mother’s love and her mother’s protection.

I also saw the public’s reaction to this. Much of it insisted on turning Alice Munro into a two dimensional bad guy, thereby refusing to face the reality that real human beings who we respect, admire, and even love take part in the sexual abuse of children, thereby maintaining the dissociative split that facilitates incest. But some of the reactions shook me, because what they were reacting to was the same behaviour that my mother so thoroughly normalizes, defends, or erases. A mutual of mine on Instagram who was a huge fan of Alice Munro’s wrote this: “it is confounding it honestly makes my fucking head explode! that a person who devoted her life to artistic truth could be so committed to denial in her own life and relationships, in basically the most devastating way possible, as her refusal to acknowledge the truth led to her decades-long betrayal of and estrangement from her child. Which was never resolved.” Reading these words I saw, for the first time, what my mother looks like from outside the realm of unreality. I saw her behaviour described with incredulity and shock. I saw it described as “devastating.”

In Andrea Skinner’s essay she writes about how her mother, who she had not told about the abuse, once talked to her about a story she’d read in which a girl was sexually abused. Munro asked her daughter “Why didn’t she tell her mother?” Skinner took this interaction, and her mother’s apparent sympathy for the abused girl in the story, as an opportunity to disclose. When she did disclose, she learned that the reason the girl in the story did not tell her mother was because she was protecting herself from her mother’s reaction. Munro reacted badly, centring her own feelings and showing no empathy for her daughter. This enormous betrayal is on par with the sexual abuse itself in how immensely damaging and painful it is.

In the aftermath of me reading this article, spinning out on the similarities with my own mother and my own life, I considered why I had taken so long to tell my own mother what my sister had told me and what I know about my father. I was protecting myself from her response. As long as I did not tell, there was always the possibility that she might react well. As long as I did not tell, there was always the possibility that she would respond with empathy and concern and horror that her daughters had ever had to live with such terror. As long as I did not tell I could hang on to the secret hope that maybe this horrible secret was bad enough for my mother to finally show empathy, to finally have an impulse toward protection. When I told and was met with cold cruelty and contempt something shattered inside of me. I don’t think I really knew what broke until I read the experience in another person’s words. The fantasy, the hope, the desperate dream of a mother who loved me enough to protect me.

Not being protected is traumatizing. Sexual abuse is traumatizing on its own. But if you were sexually abused but then protected as soon as another adult became aware, you will recover from the trauma far quicker. It is the relational wound of being unloved and unprotected that is so profoundly damaging. Not being protected is degrading. It is humiliating. It turns you into a person with no boundaries and no self-esteem. It turns you into a person with no impulse toward self-protection and you will be abused over and over again. I was. Being sexually abused strips you of your dignity, and not being protected announces that you have no dignity to protect. Not being protected communicates to you that you don’t matter and you aren’t loved.

I thought if I loved my mother enough maybe she would love me. I thought if I protected my mother enough maybe she would protect me. I thought if I understood my mother enough maybe she would understand me. I thought if I mothered my mother enough maybe she would mother me. I never blamed my mother but she blames me. When I tell the truth she blames me. And this is the most painful thing for me to face: it is not the monstrous mother who is the scapegoat in my family, it is me, the monstrous daughter. The crazy one whose many trips to the psych ward are not cause for concern or empathy but evidence of my inherent badness. There is something wrong with me. I am profoundly selfish in the expression of my pain (How could you do this to your mother?). I am fundamentally untrustworthy in my telling of the truth (delusional). And it is me who was taken by a police officer and incarcerated in a psych ward. None of the sexually abusive men in my family were ever taken away by a cop or locked up anywhere. It is me, the monstrous daughter, the scapegoat, who is blamed.

What you say about the enormity of the wound of not being protected, of your disclosure being dropped like a hot potato by the mother you disclosed to, is absolutely true to my experience.

My own mother is a mental health professional and that has been a very sour irony in my life. I can relate to the bewilderment and disappointment of witnessing an expert mother refuse to bring her expertise to bear in her own home.

…In my own mother’s defense, she never threatened to use her connections to assassinate my character simply because I needed to tell my own story. I support your decision to revoke the anonymity you’ve tended to on your mother’s behalf for so long: at this point that shield hurts you much more than it helps her.

If you can be the kind of mother to your child one day that you are to yourself today, the very least we can say is that your child will have a protector that you did not.

I’m so sorry. I can barely wrap my mind around the enormity of your mother’s response to your trauma—even if she herself was abused and not protected. The similarities between her and Munro, who was such a brilliant observer and translator of the human heart, are stark and shocking. I’m so sorry for all this pain—and I think your courageous decision to stop protecting her is a step towards healing.