The humiliation of desire

On asking for what I want

One of my earliest memories: We had a pile of picture books in my house as a child. Most of them were stories, but some of them described activities that you could do instead. When my mom told me to go pick a story to read, I would bring her one of the books that described fun, collaborative activities. Every time I would do this, she’d think I’d made a mistake and would say “this one is not a story book, go get another.” I would do as instructed. Yet I would consistently bring one of the activity books first, when asked to pick a story book, not because I was confused or making a mistake, but because I wanted to do the activities with my mom and I was hoping that one day she would look at the book and instead of saying “this one is not a story book, go get another,” she would say “let’s try some of these fun activities.” But for some reason, it did not seem like a possibility for me to say “mom, can we try some of these activities?” I was under the age of 5, based on where we were living at the time, and I had already deeply engrained the message that I should not ask directly for what I want, but instead set up the circumstances that seemed most likely for me to get what I want without having to ask for it.

This is an absolutely unnatural thing for a child to do, and it’s an unnatural thing for a person to do. Why would I, at five years old, be trying to manipulate my mother into doing an activity with me? Why did it feel so impossible, and under that, so unsafe, for me to say “mom I want to do one of these activities”? I never once asked her to do the activities. I just kept bringing her the book, over and over and over again, and every time she said I’d made a mistake, I wouldn’t correct her. I would put the book back, and next time, I would try again. We never once did one the activities from the books.

My father had explosive and unpredictable anger. I was yelled at by my father for expressing emotions. I remember my mother telling me, in that same house I only lived in until I was five, to stop crying before my dad got home, because he would think I was still crying about something that happened earlier. I learned that my inner experience was something I had to manage and hide. I learned that my emotions and desires incited anger and punishment. I learned that vulnerability was risky and I hardened myself as best I could. My parents, both of them traumatized themselves, were not attuned to me and my home environment was not one in which my authentic expressions were welcomed and safe. I learned that I had to do things in a backwards, round about, sneaky way. If I wanted to influence outcomes, I could not do so directly.

I don’t know exactly how I learned this, but I learned that expressing desire made me weak and put me in danger. To express desire exposed me, and opened me to humiliation. I learned that to admit what I want is to be humiliated. Admitting desire, I believed (and to some extent still believe), can and will be used against me. If I don’t experience anger, disappointment, or punishment in response to my authentic expressions, then I might experience something far worse: ridicule, contempt, mockery, the use of my desires to put me in my place. Admitting desire is showing your hand, baring your throat, lying belly up. And I learned it was a bad idea.

For years and years I could barely order food at a restaurant. I found it unbearable to say what I wanted, and even more unbearable to hear that what I wanted wasn’t available, because it drew humiliating attention to my unfulfilled desire. I’m good at unfulfilled desires — I’m good at not getting what I want, never even admitting I want it, going hungry, going without — but I believe this must be done in secrecy. I still cringe at direct questions about what I want. I often say nothing in response to these questions, letting the silence stretch on uncomfortably long. When I was a teenager I couldn’t eat in front of people. The act of wanting was so humiliating that I could not stand to be witnessed in it. And this, obviously, created even weirder situations that made people quite uncomfortable. For years I would not assert my will, refusing to take any of the responsibility of deciding what to do or where to go or what to eat. I tried to cover and hide and bury my desires completely because revealing them made me feel unbearable shame.

If I really wanted something then I learned to play the long game. Bring the book over and over again, and when that signal was not understood, put the book back. Hope, wordlessly, that one day, through thought and prayer and intention, and then later, through strategy and manipulation, maybe maybe maybe I would get what I want. It was confusing and counterproductive, because while I played the long game toward my desires, I actively did everything in my power to hide my desires. I needed to get what I wanted without ever showing that I wanted it, or not get it at all. This behaviour is so engrained and unconscious that even after so many years of therapy and challenging myself and working on it and learning how to be direct, I will still sometimes unconsciously send out signals that are the exact opposite of what I’m feeling. I will still sometimes say nothing or anything else, than admit the horrifying secret of my desire.

The feelings that come up for me, when I face the vulnerability of admitting desire, are not just shame and humiliation, but revulsion. I feel absolutely repulsed by the weakness and humiliation of laying bare this thing I feel compelled to hide. And then I feel anger, and then rage. A part of me lashes out at myself, telling me not to need anything, not to want anything, and if I must, then to at least have the self respect to never admit it.

I must admit that all of this has caused me to act very strange.

I have come extremely far, and every time I state my desires and preferences plainly is a huge accomplishment. Sometimes it still doesn’t feel like an accomplishment. Sometimes it feels like defeat. But I have had to let go of the idea that if I just keep trying then maybe one day I might get what I want without ever having to say that I want it. Not only is this insanely unfair to the people in my life, who don’t want to bear the responsibilities of agency and desire alone, who are utterly confused by my utterly confusing signals, and who don’t want or deserve to be manipulated by dishonesty and strategy — but it also causes me to invest in relationships, dynamics, and situations that will never ever give me what I want, and also, in the past, to stay in relationships with people who absolutely would ridicule me, humiliate me, and use the vulnerability of my desire against me.

It is so important for me to find the courage to tell the truth. I owe that respect to the trust worthy people in my life, and telling the truth is the fastest way to find out who is not trust worthy. I owe it to myself, so that I have the information I need to make the best choices for myself, to decide which relationships, dynamics, and situations work for me and which don’t. I need to hear no without being humiliated. I need to compromise and negotiate and find where desires overlap and where they diverge. I need to hear yes and feel the simple joy of that. I need to tell the truth.

It’s not a skill that comes easily to me because it’s something I learned very, very young never to do. My whole life I have been contorting myself to avoid it. For the last decade I have been actively working on getting better at it and in so many ways I have succeeded and in others, I still cringe and feel like I’m going to die, but I try anyway.

Very often, the moment in which my desire rises to the surface comes and goes without me saying anything. Sometimes the silence is too thick, too heavy, and it feels impossible to push my way through it. Sometimes I make some kind of fractured attempt, circling around what I’m trying to say. Sometimes I act extremely and unnecessarily weird, making an abnormally big deal out of the situation, only to finally spit it out and have the person say — “that’s it? that’s the thing?”. Very often, I have to returne to the desire later because I couldn’t say it at the time. Writing it and sending it as a text is often easier, and it is a way to practice and get better at the skill.

I’m getting better at it. Certain desires are easier than others. Certain contexts are easier than others. The more I want it, the harder it is to say. But I work on it. As a commitment to myself and who I want to be in the world. As a commitment to the people in my life who deserve my honesty and clarity. It’s not easy.

But I want to change.

Announcements and new things

Reclaiming Our Power: A special workshop for women by Clementine Morrigan at Breitenbush Hot Springs in Oregon, USA, in March 2024 — Limited spots available.

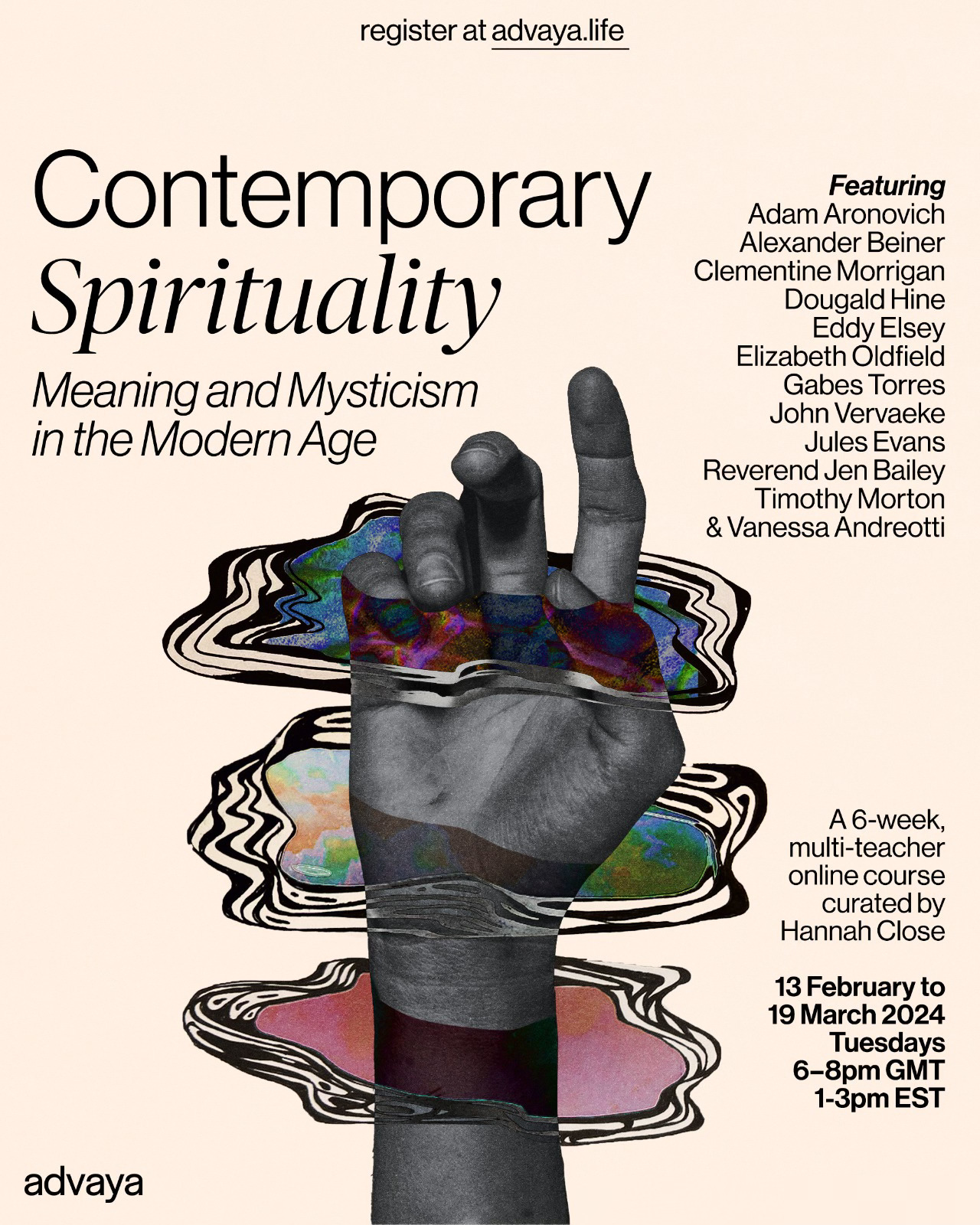

Contemporary Spirituality: Meaning and Mysticism in the Modern Age (Upcoming course I’m teaching in) — Use the code TEACH-CS-MORRIGAN for a discount.

Things I’m reading, listening to, watching or thinking about lately

'Green' Elites vs Green Left Populism by Jay Lesoleil

Hating Others is Self Harm by Flora Hibbs

Heat stress and fetal risk. Environmental limits for exercise and passive heat stress during pregnancy: a systematic review with best evidence synthesis by Nicholas Ravanelli, William Casasola, Timothy English, Kate M Edwards, and Ollie Jay

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara

South Africa says Israel is committing genocide in Gaza by Nick Logan

Namibia condemns Germany for defending Israel in ICJ genocide case

Featured from the shop

This is my favourite zine in this zine series because it’s the most recent and so therefore my ideas are the most developed. Get yours in hard copy or digital.

This zine is a series of essays challenging the repeated arguments in favour of cancel culture: that is doesn’t exist, that it’s about justice, that it’s our only effective strategy for taking abuse seriously, that it’s an important tool for marginalized people. The essays explore different elements of cancel culture and of the questions cancel culture claims to answer. Overall it makes the argument that cancel culture is absolutely at odds with an ethics of abolitionism, that is an ineffective tool for ending abuse, that it actually creates new forms of abuse, and that it is ultimately bad for the goal of a creating the broad based movement of workers needed to pose a threat to capitalism and change things. Who should define accountability? How do we create cultures of consent? What does it mean to ‘believe survivors’? Who is to blame and where should we direct our anger? How can we move toward a world where no one is disposable and everyone is treated as a full complex human being? Why is cancel culture a problem for the Left? These and many more questions are explored in the pages of this zine.

Clementine Morrigan is a writer and public intellectual based in Montréal, Canada. She writes popular and controversial essays about culture, politics, ethics, relationships, sexuality, and trauma. A passionate believer in independent media, she’s been making zines since the year 2000 and is the author of several books. She’s known for her iconic white-text-on-a-black-background mini-essays on Instagram. One of the leading voices on the Canadian Left and one half of the Fucking Cancelled podcast, Clementine is an outspoken critic of cancel culture and a proponent of building solidarity across difference. She is a socialist, a feminist, and a vegan for the animals and the earth.

Browse her shop, listen to her podcast, book a one on one session with her, or peruse her list of resources and further reading.

oof. while I deeply resonate with the stories (I too am an expert at what Marcia Brzezinski calls desire "smuggling"), the idea of expressing desire as opening to the possibility of humiliation deepens my understanding of the phenomenon. thank you for that. this remains an area of deep inquiry for me, sharing some thoughts in case they are helpful for others feeling into the radical potential of desire: https://citizenstout.substack.com/p/the-audacity-of-desire

HOMIEEEE, "Sometimes I make some kind of fractured attempt, circling around what I’m trying to say. Sometimes I act extremely and unnecessarily weird, making an abnormally big deal out of the situation, only to finally spit it out and have the person say — “that’s it? that’s the thing?”. Very often, I have to returned to the desire later because I couldn’t say it at the time."

Your words elaborate on a specific layer of depth in the experiences and feelings I've had for so long, yet I never realized it existed until reading your writing. Your writing is full of gems.