CHILD SACRIFICE

Incest and chronic shame

It is well known that survivors of sexual violence, and in particular, survivors of child sexual abuse, live with chronic shame as a result of these traumas. While there is a lot written on the impacts of living with chronic shame, there is little written on why these experiences cause shame. It seems as if we’ve all agreed it goes without saying. Of course being raped, or being sexually abused within the family would cause shame. Of course sexual violation would cause shame. Of course the breaking of the incest taboo would cause shame. But why?

It seems we’ve settled for the vague explanation that sexually violent acts are seen as “dirty” (due to their connection to sexuality?) and that the act of being sexually violated therefore contaminates the victim. Or maybe it’s that the helplessness of the victim position is inherently seen as shameful. In the case of incest, because we see incest as disgusting, it makes sense that being a victim of incest would result in shame. All of these explanations are more often alluded to than stated outright. The culture adds to the shame of victims by not taking the question of shame seriously. The culture seems to say — of course it’s shameful. Obviously.

Shame is a complex emotion that seems to serve the evolutionary purpose of signalling when we have behaved in ways that are dangerous or damaging to the collective. Guilt also signals behavioural infractions that should be remedied, but shame indicates behavioural infractions that are so dangerous or damaging they could result in expulsion from the group (the most serious consequence possible for a social primate). Shame is fundamentally tied up with the question of belonging. When we feel shame, we feel fear that we will be rejected from belonging. As social primates, shame is functional insofar as it shows us how to behave in ways that keep the group together and functioning. Shame says you’ve violated a fundamental social code and creates an imperative to return to pro social behaviours.

The chronic shame that results from surviving sexual violence or incest is something different. Chronic shame creates a permanent sense of being outside of the collective. The message of chronic shame is There is something wrong with me. Rather than being a temporary rupture that can be repaired, or warning that can be heeded, chronic shame communicates permanent outsider status. Chronic shame is a permanent feeling of not belonging that seems to stem from an inherent badness, wrongness, or unworthiness.

Sexual violence is annihilation. Sexual violence communicates that your value as an object for sexual use eclipses your value as a human being. Everything fundamental to human dignity: recognition of complex, unique, irreplaceable personhood, protection of vulnerability, the right to privacy especially with regard to the body and sexuality, and the right to bodily autonomy, are exchanged for the pleasure of sexual domination on the part of the perpetrator. Nothing could be more degrading than the message that everything precious and sacred about you matters less than the perpetrator’s sexual desire.

If the collective steps in to prevent or stop the sexual violence, and communicates clearly that the shameful act is the (attempted) perpetration, the victim will probably not develop chronic shame. The collective has the power to prevent chronic shame by countering the degrading message of sexual violence. The collective can say: this is an irreplaceable human being deserving of protection, privacy, and autonomy. The collective can say: it is unacceptable to treat a human being as an object for sexual use. It is wrong. If the collective steps in to rigorously defend and protect the dignity of the victim, chronic shame will probably not develop. The victim will receive a different message: I belong. I matter to the collective. My humanity is worthy of protection and defence. The value of my personhood cannot be reduced to the use value of a sexual object. I am protected. I will not be annihilated. I am seen.

Chronic shame, which communicates a permanent state of badness, wrongness, unworthiness, and outsider status, is the natural reaction to experiences that teach you that your humanity is less valuable than the perpetrator’s sexual pleasure. If the collective fails to counter that message, or worse — strengthens the message by normalizing the violence, demanding submission, or blaming the victim, chronic shame will develop.

In the case of incest, the degrading message of sexual violence is compounded for two reasons. The first is that the victim is a child. Children are supposed to be protected and cherished. Children are supposed to be valued not only as human beings but as children. The vulnerability of children is supposed to be protected, not exploited. The collective is supposed to protect, love, nurture, and cherish the most vulnerable among them — the children. To learn, as a child, that you are more valuable as a sex object than as a child is devastating beyond comprehension.

The second compounding factor is that the sexual abuse is taking place within the family. The family is the place where you are supposed to be safest. The family is the place where you are supposed to be the most loved. The family is the place where your irreplaceable personhood is supposed to be the most cherished, the most valued. We all know that we are much more affected by the news that a loved one is in danger than a stranger. The fact of being a “loved one” is supposed to grant a special status. You are supposed to matter to your family, deeply. The message that you matter more to your family as a sexual object than as a daughter, granddaughter, or sister, is devastating beyond comprehension.

Incest is a family system. It is not a discrete act of perpetration enacted on the victim. I do not believe anyone who says that sexual abuse within the family was “unknown” to the other adults within the family. It is time for us to dispel with the mythology that “they didn’t know.” Incest is carried out with varying degrees of secrecy but it is never actually a secret. Incest is an intergenerational pattern of violence and trauma that relies upon and creates pervasive dissociation within every member of the family. In some families, the sexual abuse is carried out in public, in front of everyone, and multiple adults take part in coercing the children into submission. In these families the sexual violence is not sexual violence — it’s harmless, it’s a “game,” it’s “just the way things are.” In other families, the sexual abuse happens in “secret” and the other adults claim they “didn’t know.” Yet the very obvious signs of child sexual abuse are ignored. Ignorance of child sexual abuse is actually something that must be actively created and maintained. It is extremely obvious when a child is being sexually abused, and adults who do not carry the incest dissociation pattern within themselves will notice and respond. In some families both strategies are present — some types of sexual abuse are carried out publicly and treated as harmless, while others take place in “secret” and everyone pretends not to know.

This situation in which the family — the people who are supposed to love, cherish, and protect the child more than anyone — allow, condone, normalize, and/or ignore the sexual abuse, creates pervasive, chronic shame. The message is clear. The child learns that they do not matter as a person; they are not worthy of protection even from the threat of annihilation; the people they love and trust most in the world expect and demand their submission to the worst possible thing. For a child, facing the terrifying danger of this situation is too much to take. Therefore the child internalizes the idea that the problem is not their abusive family (over which they have no control) but themself. The development of chronic shame starts out as an adaptive strategy: if the problem is me, then maybe I can change it. If the problem is that I am unworthy of love and protection, then maybe I can become worthy.

This betrayal by the other adults in the family is as traumatizing, and sometimes even more traumatizing, than the sexual violence itself. The American Counseling Association notes “in cases in which a mother chooses the abuser over her daughter, the abandonment by the mother may have a greater negative impact on her daughter than did the abuse itself. This rejection not only reinforces the victim’s sense of worthlessness and shame but also suggests to her that she somehow “deserved” the abuse.” The source of chronic shame is not just the sexual abuse itself but the collective agreement that the sexual abuse is acceptable. There is no way for a child to make sense of this level of betrayal other than to internalize it as a pervasive, and chronic, sense of shame.

Years ago, I was watching the show Game of Thrones. While many of the scenes obviously disturbed and upset me, one scene affected me so profoundly that I had to stop watching the show. I had intrusive thoughts about the scene for a long time after watching it and it plunged me into an unbearable and complex emotional experience. The scene in question involved a child being burned alive by her parents as a sacrifice in order to ensure victory in war. The child cries out and pleads with her parents as they, and a crowd of onlookers, watch her be burned alive. There were many extremely disturbing scenes in Game of Thrones, including many that show sexual violence explicitly. I didn’t know, at the time, why this scene in particular affected me so profoundly.

I now realize that this scene perfectly illustrates the emotional experience of incest. Incest families have many strategies for justification, minimization, and denial, but the reality is that in incest families the children are sacrificed. The children are annihilated. The children are made to experience mindbreaking horror while everyone they love and trust look on. The child must be sacrificed for the cohesion of the incest family system. The incest perpetrator demands the child sacrifice and the rest of the family agrees that it is necessary. This experience of being the child sacrifice, of having your personhood offered up in exchange for the perpetrator’s pleasure in sexual domination while everyone you love and trust accepts it as a necessary sacrifice, is the emotional experience of incest and the source of chronic shame.

The result of this trauma for many survivors is a dangerous combination of low self esteem, no capacity to set boundaries, and no sense that you should be treated well. Because you were violated and betrayed in the most profound way possible by the people you trusted most, and this was treated as normal or unimportant, you will have no ability to discern safety from danger. This is why survivors of incest go on to be abused over and over again. This experience of revictimization further entrenches the chronic shame. The world seems to be offering up endless proof that you really are unworthy of love and protection. Additionally, survivors of incest often become addicted to drugs or alcohol, have sex for money, live in poverty, and/or develop chronic illnesses — all shamed experiences. The very evidence of being an incest survivor is considered shameful by society.

Many well meaning people suggest that our response to this situation should be to put the shame “back where it belongs” by assigning it to the perpetrator rather than the victim. This seems to align with the evolutionary function of shame as a deterrent to antisocial behaviours. However, what this strategy misses is the reality that the perpetrators already feel chronic shame. They don’t feel shame for their sexually abusive actions (the chronic dissociation and normalization of sexual violence protects them from this) but they do feel the same chronic shame that they are now creating in their victims. Shame is the emotional heart of incest as a family system. Every perpetrator of incest was introduced to sexual abuse as a child, probably within the family. Whether they were being directly sexually abused themselves, or witnessing sexual abuse within the family, they were indoctrinated into the message of the incest family system: children are to be sacrificed — annihilated — and everyone will accept this. The dissociative strategies necessary to cope with chronic shame feed back into the incest family system. If we want to end incest, we have to end dissociation. If we want to end dissociation, we have to end chronic shame.

This does not mean that we must love or forgive our perpetrators. It does not mean that our perpetrators are not responsible for their actions — they are. Or that the act of sexually abusing a child is not shameful — it is. In fact, the sexual abuse of children, like rape, murder, or cannibalism, is the type of antisocial behaviour that shame probably evolved in our social species to dissuade us from. Rejection from belonging within the collective — the most serious consequence for our social species — is, to some degree, appropriate in situations of child sexual abuse. Adults who have abused children or allowed children to be abused should no longer be allowed access to children. Their adult victims have the right to decide to no longer have relationship with them. The larger collective should have access to information about the abuse in order to ensure the protection of children. Some form of organized separation that prevents access to children is necessary.

However, we cannot simply wash our hands of perpetrators — shame them, incarcerate them, ostracize them, or murder them — and think we have solved the problem. The same problem now exists in their victims. That doesn’t mean that victims will necessarily become perpetrators, but they are at a much higher risk of becoming perpetrators, dissociatively “not seeing” and allowing abuse, and/or being revictimized themselves. Incest is a family system. All perpetrators and enablers were once victims. All victims are at a high risk of perpetuating the system in some form unless they do what they need to do to break the cycle. The problem won’t just go away. We have to face it.

Shaming incest perpetrators (incest survivors) is like pouring gasoline on a fire. It will only increase the dissociation that leads to more incest. We can’t give the shame back because the shame already permeates the entire incest family system. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be honest or expressive in our anger or disgust. That expression is a necessary part of recovery for incest survivors. It doesn’t mean that we must tip toe around the feelings of our abusive families either. We do not need to police our expression in an attempt to protect perpetrators from their own shame. But we do need more effective strategies for ending the cycle of incest. Shame will not cut it. The antidote to the chronic, intergenerational shame and dissociation of incest families is not more chronic shame and dissociation. The antidote to shame is dignity. The antidote to dissociation is truth.

The truth of the incest family system must be spoken out loud, for what it is — not a discrete relationship of perpetration and victimization, but a family system — a pattern of intergenerational violence, dissociation, and shame. A light must be shone on the existence of other examples of incest and sexual abuse in and around the family. Dorothée Dussy, author of Le berceau des dominations, discovered in her research that incest families frequently include an unusually high number of early and violent deaths. These suicides, “accidents,” overdoses, and murders must also be seen, understood, and recognized as part of the incest family system. They are evidence of incest. They are the result of incest. The normalization, minimization, denial, and silencing of incest must be shattered. Incest must be spoken out loud, publicly. All the out of print books on incest must be put back into print. We must interrupt the practice of collective forgetting and repression. Incest must be faced, and seen, in complete detail, for what it is. Not just in each incest family, but in the larger culture that contributes to the dissociation, because the culture is made up of many incest families and non incest families take part by not getting involved and looking away. By minding their own business. We must make the abolition of incest everyone’s business.

The restoration of dignity flows from facing the shattering grief and horror of what has really happened. It is only when we face the lie of chronic shame that we can get underneath it and see the extent of the atrocity. Being good will never solve the problem because the problem is not that I am bad. We must face the lie of chronic shame, the adaptive strategy of an abused child, and realize that the problem was never our fundamental unworthiness, badness, unlovability, but that we were children held captive in an incest family system, where all of the adults were dissociating and reenacting a pattern of intergenerational violence, trauma, and chronic shame. We must restore our dignity by grieving that it wasn’t protected, and by facing the truth that we were violated and betrayed in the worst way possible by the people we loved and trusted the most. Dignity is restored when we see the irreplaceable singularity of every human being, including ourselves. Dignity is restored when we see the enormous pain of every abused child and we commit ourselves to creating a world where this never happens again.

Part of this work is honouring the dignity of survivors. What I mean by that is that survivors need not only to have our dignity as human beings restored, but we must now carry a new kind of dignity — the dignity of survivors. Honouring the dignity of survivors means recognizing and meeting the specific needs that survivors have. It means developing cultural literacy around survivors. It means not assuming someone had a loving family because many people did not. It means not assuming that someone’s introduction to sexuality was positive or benign because for many people it was not. It means normalizing that incest survivors may have different needs around our boundaries, our social interactions, our sexual and romantic relationships, and our community involvement. It means making it socially acceptable to talk about those needs and why we have them. Honouring the dignity of survivors also means welcoming and valuing the specific gifts and knowledge that survivors carry. Survivors who have faced our trauma are deeply wise and hold profound lessons for humanity. Rather than being pitied or shamed for what was done to us, we should be honoured, respected, and listened to for the work we had to do in order to break the cycle.

Finally, no piece of writing on child sacrifice and chronic shame can be complete without mentioning the children of Palestine and the horrors being inflicted upon them in front of the eyes of the world. Racism, like sexual violence, is annihilation. Everything fundamental to human dignity: recognition of complex, unique, irreplaceable personhood, protection of vulnerability, the right to privacy especially with regard to the body and sexuality, and the right to bodily autonomy, are exchanged for the pleasure of (often sexualized) domination on the part of the perpetrator. Even children are stripped of their inherent right to protection and dignity in the face of racism. It is no surprise to me that Israel, a genocidal and racist state built on the displacement, dehumanization, and mass murder of Palestinians, relies on sexual violence and the most extreme forms of violence against children imaginable to carry out its genocidal aims. Israel, much like an incest family system, runs on intergenerational trauma and mass collective dissociation. We, the collective, must intervene. We, the collective, must insist, with all the force possible, that Palestinians are human beings who do not deserve to be tortured and murdered. We, the collective, must insist, with all the force possible, that Palestinian children are children and they must be cherished, protected, and loved, not violently sacrificed in the name of genocidal domination. Our responsibility toward the Palestinians begins with stopping the genocide but it does not end there. Through a similar process to what I described above, we must interrupt the development of chronic shame that results from being subjected to such violence in the face of so many witnesses, by intervening, by telling the truth, and by redignifying all survivors of genocide, imperialism, and racism. Racism must be abolished.

Chronic shame has debilitating health effects, creates chronic inflammation in the body, creates chronic illness, and shortens lifespan. Chronic shame results in a whole range of behaviours and survival strategies that increase the risk of revictimization, perpetration, and dissociative inability to appropriately intervene on violence. Chronic shame is a public health issue. Incest is not the only system that creates chronic shame but chronic shame is the heart of the incest family system. We must make incest something that can be spoken, publicly. We must not shy away from this topic because it makes us uncomfortable. We have an ethical, moral, and political responsibility to end the systematic silencing of incest survivors and public discussions of incest. We have an ethical, moral, and political responsibility to take up the abolition of incest as a collective cause. Together we must insist: Not one more child will be sacrificed.

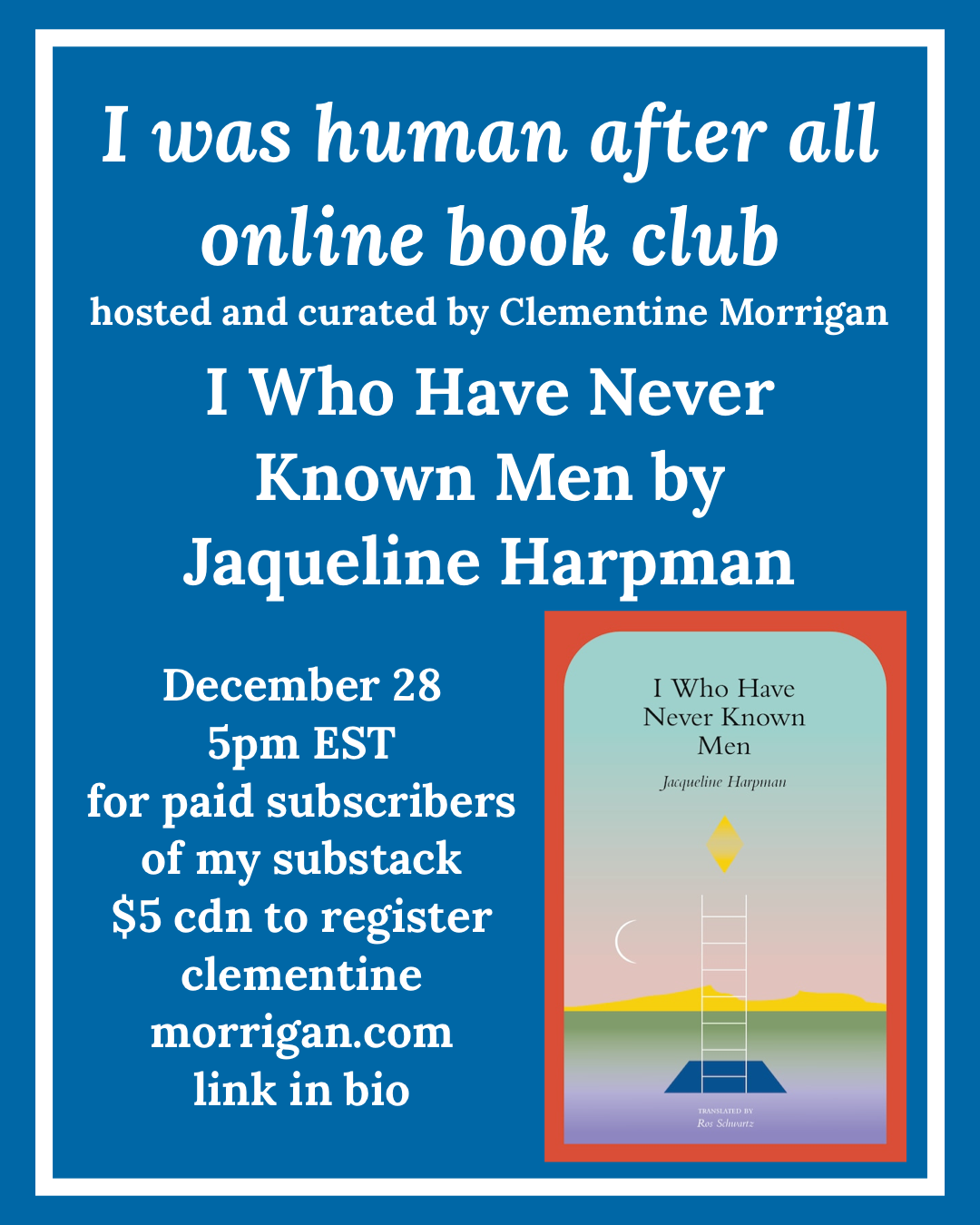

Join us on December 28th at 5pm EST to discuss I Who Have Never Known Men by Jaqueline Harpman. The zoom link will be sent out via this substack, or find it at clementinemorrigan.com on the 28th.

Order my new book, Fucking Magic, here.

Order my new book, L’art oublié de baiser, here.

Pre-order my forthcoming book, Love Without Emergency, here.

Clementine Morrigan is an underground writer, cultural change maker, moral philosopher, and brazen truth teller. She is the author of numerous zines and books, including the cult classic zine Love Without Emergency, which will be released as a book with Microcosm Press in 2027. Her popular zine series Fucking Magic was released as a book with Revolutionaries Press in 2025. She co-hosts the podcast Fucking Cancelled with Jay Lesoleil. Her work is known for its unflinching engagement with taboo and difficult topics. She works for a world where the dignity of all beings is recognized and protected.

So brilliant. Emotional incest confused me about which feelings were mine and which were my mother's. Part of the purpose of abuse is to make someone else a storage container for your unbearable feelings. So the victim is holding the perpetrator's shame as if it were their own. (In addition to everything else you described.) As a person of Jewish heritage, I am so angry and sad at how Israel and its supporters are re-enacting our historical trauma.

Wow, yet again you put words to something that feels impossible to describe. I have spent so much of therapy talking about how I see myself as an object, which has made me feel so much shame for internalizing that message. Thank you for the reminder that my experience is not unique and that CSA inherently instills that message. Thank you for yet again helping me feel a sense of belonging through your work.