Whatever it is, you can face it

On our fundamental and irrevocable belonging to this world

The first truth: There is nothing in this world, nothing you have done, and nothing that has been done to you, nothing that you failed to do or that you did not receive, that could ever threaten or take away your inherent worthiness, your fundamental belonging to this world.

This is the starting place. Before we understand this, individually, we are incapable of taking true responsibility for anything, we are incapable of being truly honest with ourselves or others, because we are threatened at the most fundamental level, the most important thing is at stake, and so we are afraid and we can’t think clearly or make good decisions. Before we understand this, collectively, we will keep threatening each other, frightening each other, traumatizing each other, punishing each other, exiling each other, and we will continue to create cultures and societies of dishonesty, dissociation, denial, defensiveness, repression, and scapegoating, because the stakes of facing reality are way too high.

Once we understand that our worthiness and belonging to the world, our fundamental preciousness and singularity, our undeniable need to be a part of human community, is irrevocable, then the work can begin. Once we know that anyone who dehumanizes us, punishes us, exiles us, scapegoats us, demonizes us, or in any other way attempts to deny this fundamental and unchanging truth, is incorrect and both can and should be challenged, then we no longer need to rely on dishonesty, dissociation, or denial to protect us.

The second truth that flows from the first: Whatever it is, you can face it. We all keep things hidden from ourselves because we are terrified to face them. We are terrified to face them because to face them will be unbelievably painful: there will be reckoning and grief, remorse and regret, horror and anguish, and a great many other natural responses to whatever it is that we have buried. But we are capable of feeling and facing all of that, and through feeling and facing all of that, we will be transformed and will find the way to integrate the truth of what has happened into our own human experience and into the collective human experience. No longer sectioned off, repressed, it can be known, and it can therefore be responded to and learned from. The reason we do not face it is not because it is so difficult to face. We are capable of doing difficult things and the rewards will be great. The reason we do not face it is because we are so afraid that to face it will mean that our fundamental need to belong to humanity will be denied. We think this thing, if it is permitted into the wholeness of our story and into the human story, will result in our expulsion from the human: the fear that there really is something fundamentally wrong with us that exempts us from the human will be proven true.

There are many things we repress and deny out of terror that they could threaten our fundamental need to belong to the human world: we deny the ways we have been hurt and the ways we have hurt others, we deny our human bodies and their aging and their vulnerability, we deny our deepest desires and greatest ambitions, we deny the unspeakable things that flood us with unbearable shame. We all bury different things, but there’s a lot in common among the buried. It’s all stuff we fear falls outside of the human, stuff we are afraid exempts us, excludes us. If people really knew me, they would not love me. If anyone ever saw this, I would not belong.

This damages us in countless ways, cutting us off from our authenticity, our integrity, and the full expression of our humanity. It prevents us from telling the truth to ourselves or anyone else about what has really happened and who we really are. It also perpetuates cycles of violence: what can’t be known, can’t be faced, and can’t be transformed. Anyone who regularly hurts others has a huge amount of repressed and dissociated content. If you know someone who behaves violently and abusively, you will see that their psyche is fractured: they both know and do not know what they are doing. In a very real way, they can’t know it. To know it threatens the most important thing: their belonging to this world. So they press it down with all their might.

There are those who believe that shame and fear of punishment and exile are useful tools for preventing people from doing highly anti-social things. These people misunderstand the human psyche and underestimate its capacity to fracture. Shame and fear of exile and punishment do not prevent anti-social behaviours and drives: they prevent the facing of anti-social behaviours and drives. They create an imperative to look away, a taboo. In this way they keep violence out of sight, underground. Denial and dissociation flourish under shame and fear of punishment and exile. People are so afraid that what they are doing or what they have done exempts them from belonging to the human that they refuse to face it. If they don’t face it, they can’t feel it, they can’t reckon with it, and they can’t transform it.

When we feed into the collective mythology that violence is perpetrated by “monsters”, by those who are somehow less than human, somehow outside of humanity, we reenforce our collective dissociation. We work together to dissociate and to deny the reality that human beings have the capacity to do horrible things. This is a part of our humanity, not outside of it. It is only when we face this, this legacy of violence and trauma that runs all throughout human history, that we can feel the pain of it, the pain we have so carefully locked in the basement.

We tell ourselves we must punish people so they will feel “bad”, but the truth is that underneath the dissociation and repression, they already feel bad. Empathy is innate. We can disconnect from it, but it still exists underground. Behind all the careful splitting is the full depth of feeling, the truth of what we have done and what has been done to us. When we face it, we bring it out of the basement and let it live in the light of day. We feel it and there is a deep and sometimes seemingly endless well of pain that must be felt. But this pain is human pain — it’s not the dissociated terror of exile that cuts us off from feeling, but the return of the repressed emotions themselves.

There is no one “too far gone” who is unable to face, integrate, and transform what has been repressed. There is no human whose story falls outside of the human: that is impossible. Facing it is not a dismissal of the seriousness of the horrors that have been locked in the basement. Facing it is finally feeling the full extent of what has been kept outside of consciousness. Facing it leads to change, to remorse, to grief, to responsibility, to action, and to integrity. When we know our human belonging is not under threat then we will do anything to try to bring our whole selves back into the human world, because that is where we so desperately long to be.

The reason this is so hard for people to believe is because we so rarely see it modelled anymore. But I have seen it. I have seen it in people working the 12 steps, who are shown that their belonging is not contingent upon denying the truth of who they are, what’s been done to them, and what they’ve done. People are emboldened and encouraged by this demonstration of irrevocable belonging. Courage blooms under those circumstances. I have witnessed people find the courage to look: to face it, reckon with it, integrate it, and transform it. The people who do this change in fundamental and sustainable ways. The people who do this find ways to make amends: they can’t change the past but they live in the present in a way that honours the past. They do their very best to give back in the places they have taken.

I have seen this in people doing psychedelic work too: psychedelics have a tendency to remind people of the truth that it is literally impossible to revoke their belonging to the world, no matter how it might seem. In the magic space of ceremony, many people find the irrevocable anchor of belonging and therefore the courage to travel down the well and look at what is hiding underground.

There are many ways to do this work, through therapy, through spirituality, through inner work, through collective work. They all include the two ingredients: first, a recognition of irrevocable belonging, second, the courage and willingness to face it all. I have done this work myself. I have travelled down to the underworld, in the loving light of my belonging, and I have faced everything I found down there. What emerges from this work is presence, integrity, responsibility, compassion, forgiveness, and grace. What emerges from this work is the relinquishing of dissociation, because everything is welcome. Nothing is turned away.

Announcements and new things

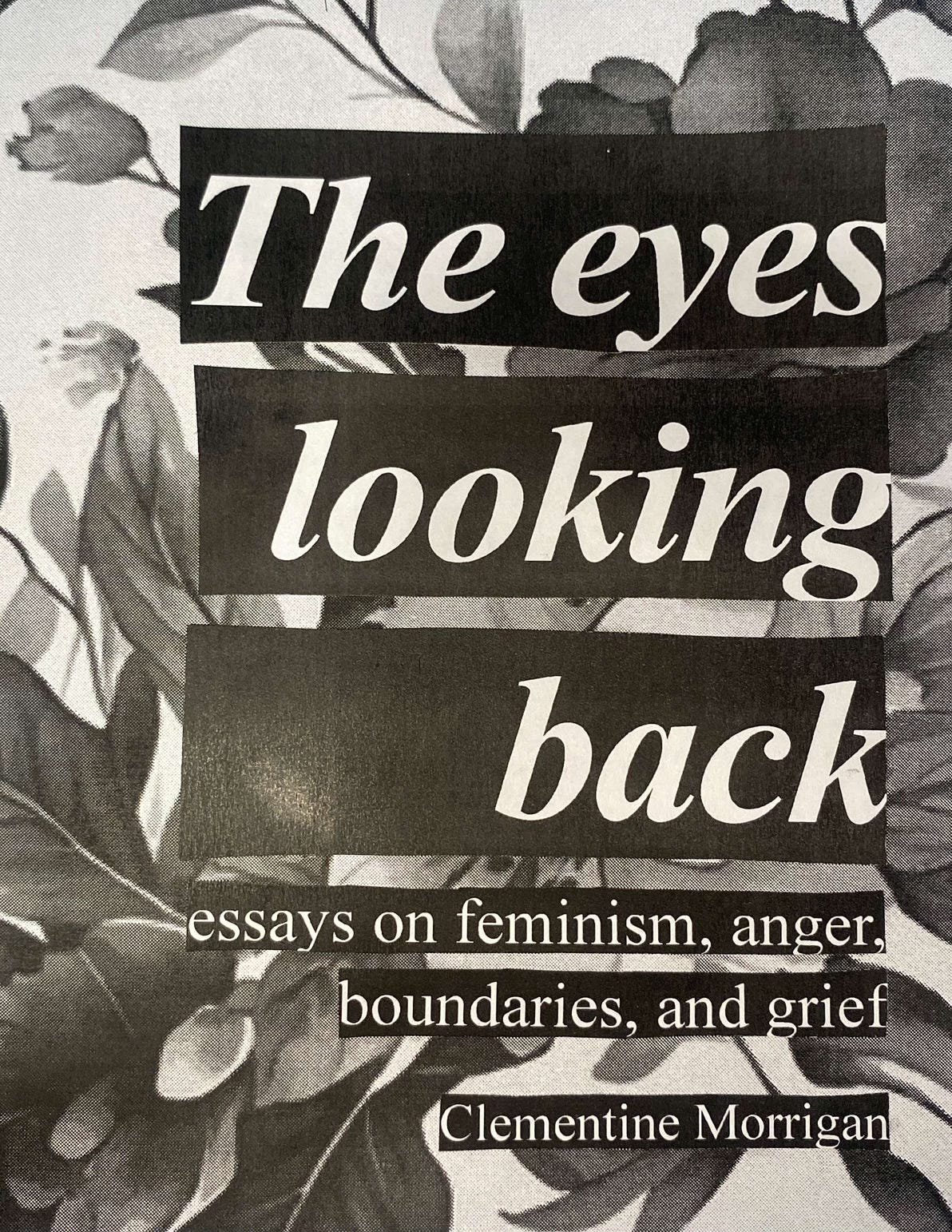

The eyes looking back: a collection of essays on feminism, anger, boundaries, and grief.

Reclaiming Our Power: A special workshop for women by Clementine Morrigan at Breitenbush Hot Springs in Oregon, USA, in March 2024 — Limited spots available.

Contemporary Spirituality: Meaning and Mysticism in the Modern Age (Upcoming course I’m teaching in) — Use the code TEACH-CS-MORRIGAN for a discount.

Controversy & the Art of Unfiltered Expression with Clementine Morrigan on the Curiocity Podcast

Talking Shit with Katherine Angel: Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again

Things I’m reading, listening to, watching or thinking about lately

On Self-Respect by Joan Didion

Equal Rites by Terry Pratchett

Featured from the shop

A new zine! Available in hard copy. Digital version coming soon.

The eyes looking back is a collection of essays on feminism, anger, boundaries, and grief. Wide ranging in their inquiries, these essays touch on the subtle sexism of self-proclaimed feminist men, the difficulty of expressing desire and setting boundaries in the aftermath of childhood trauma, the psychiatrization of trauma and the junk science of the DSM, the experience of sexual assault through negligence rather than malicious intent, and the grief and pain of constrictive gender roles, heteronormativity, and objectification. These essays are compassionate and curious while insisting on the importance of anger and the necessity of telling the truth.

List of essays

When you say I seem angry, I get more angry: Why your anti cancel culture fave is still a fucking feminist

The substitutes we accept for love

Sexual assault through negligence

As forcefully as the moment demands: On boundaries, anger, and messy break ups

I'm so angry, I don't think it will ever pass

The humiliation of desire: On asking for what I want

Other people's disappointment

The eyes looking back: On my refusal to be an object and what this can sometimes make men feel

Clementine Morrigan is a writer and public intellectual based in Montréal, Canada. She writes popular and controversial essays about culture, politics, ethics, relationships, sexuality, and trauma. A passionate believer in independent media, she’s been making zines since the year 2000 and is the author of several books. She’s known for her iconic white-text-on-a-black-background mini-essays on Instagram. One of the leading voices on the Canadian Left and one half of the Fucking Cancelled podcast, Clementine is an outspoken critic of cancel culture and a proponent of building solidarity across difference. She is a socialist, a feminist, and a vegan for the animals and the earth.

Browse her shop, listen to her podcast, book a one on one session with her, or peruse her list of resources and further reading.

This post saved me. I cant than you enough.

"When we feed into the collective mythology that violence is perpetrated by 'monsters', by those who are somehow less than human, somehow outside of humanity, we reenforce our collective dissociation. We work together to dissociate and to deny the reality that human beings have the capacity to do horrible things. This is a part of our humanity, not outside of it."

💯 This is EVERYTHING. Once I really understood this in my very cells, my relationship to disowned parts shifted dramatically. I have found deep support and refuge in community for this work in particular.