I chose empathy

Part two

Read part one here.

I became a vegetarian when I was six years old. Once I understood what “meat” was, I wanted no part of it. As I got older I learned that more and more ingredients in the food I ate were produced through torture. I remember being maybe 8 or 9, walking with friends, eating a chocolate bar that had marshmallow in it. One of the other kids said to me “I thought you were a vegetarian? Marshmallow has gelatin.” This wasn’t said in a compassionate way, one animal lover to another, it was said in mockery — a gotcha moment to lord over the too sensitive vegetarian. I remember the panic in my body. The horror. I said nothing. I waited until I got home. I knew there were marshmallows in a cupboard at my house. I ran to the cupboard, pulled out the plastic bag, my eyes frantically scanning the tiny text. There it was — gelatin. I collapsed on the ground sobbing.

Few people would understand this reaction. It is treated as extreme, dysfunctional. To me, it is the most natural reaction in the world. Of course I would respond with terror and irrepressible grief that every day, against my will, I was brought into complicity in the torture of billions of animals. I loved the animals. I loved the dogs in my family. I loved the birds and deer and racoons who lived in the forest. Of course I loved the pigs and cows and chickens. Of course I knew that they did not deserve to suffer and die having never been allowed a life of their own. Of course it filled me with pain of unimaginable proportions — not only the horror of the atrocity but the fact that every single person seemed to think it was okay — right — and that it was my empathy with the animals that was an aberration.

I understood the normalization of torture all too well. I understood captivity. I was a child trapped in a house with a pedophile. My grandfather preying on me while every single adult acted like it was normal — right — that he did so. My terror, my outrage, my attempts to escape or fight back were the aberration. And I was subjected to constant brainwashing, constant training to repress my right and natural instinct to resist the violence. My family insisted that what was happening was normal, that it was my reaction that was abnormal and extreme. Just like with the animals, the violence was just the ways things are, natural and protected, and my opposition to the violence represented a kind of immaturity that I would need to learn to grow out of.

By the time I was fourteen I was parroting the same brainwashing statements my father made to me to my little sister. My little sister and I were in a bad position, two children being preyed upon by our grandfather and forced into submission by our father. I tried to protect her but I also argued with her over who had to sit next to Bapa in the truck. We had to hold on to the reality of our terror with everything we had because we were punished for it. Our father repeatedly screamed at us for being selfish, disrespectful, ungrateful. I trained myself to repress my disgust, repress my fear. And then eventually, I started to take part in my sister’s brainwashing. I remember responding to her complaining about my grandfather by telling her to be grateful, to be respectful. I remember telling her there were homeless people in the world, people with much bigger problems, and we should stop complaining and be good.

One of the features of complex trauma, a type of trauma that results from captivity, from being unable to escape the nonstop violence to the point where it becomes normal and the victim eventually stops fighting, is identification with the perpetrator’s worldview. I was identifying with my father’s worldview by taking part in the disciplining and brainwashing of my little sister. Later, after I went “crazy,” I very intentionally tried to kill the empathy in my heart. I believed the only way I would survive my grandfather, and my father, and all the men like them, was to become like them. I drank copious amounts of alcohol and unleashed my rage upon the world. Not just against the perpetrators but against the victims too. We want to believe that there are good victims and bad victims, and that good victims never become perpetrators, never take on the worldview of the perpetrators, but this is a refusal to understand what trauma is and how it works. Not all victims go on to repeat the cycle but many do, in all sorts of ways. This is not because these victims are essentially bad and undeserving of compassion. It is because trauma shatters you. We find all sorts of ways to survive — including trying to kill off the best of ourselves.

I became a vegan when I was sixteen, when I finally understood that the dairy industry and egg industry are not the cartoon images of happy cows and chickens but are industries built on unthinkable cruelty and torture just like the meat industry. When I was nineteen and in the throes of alcoholism and violence, I was trying to crush the empathy in my heart. I would literally read websites about “how to be a man.” I wanted to study them and become like them. When I was 19, at a local hardcore show, I was dragged down the stairs on my back by my pigtails with my breasts pulled out of my shirt while everyone watched. I could not afford to be a “woman” any longer, at least not in the way I had learned to be a woman. I could not afford to be good. I could not afford to be soft. I could not afford to care about anything. I believed I needed to kill all of that out of me. I believed I needed to become meaner and crueller and colder than the men. I needed to do it back to them. I needed to show them there was nothing in me left to hurt because I had killed it myself. And so when I was 19, I forced myself to start eating dairy and eggs again.

It viscerally disgusted me to eat the breast milk of tortured cows and the eggs of tortured chickens. But I told myself that personal pleasure was more important than empathy. I made lists of “delicious” foods that I would be able to eat now. I told myself the freedom and convenience was personal empowerment and the deep empathy I felt for animals represented vulnerability and weakness. I watched horror movies with my sister to numb myself to violence. I started to hold up Leatherface from the Texas Chainsaw Massacre as an emblem of empowerment. I needed to embrace the horror, become the horror, become the violence. I needed to kill whatever was left in me that still cared about anything. I called myself Clementine Cannibal (it was myspace era) and I worked hard to cultivate a persona that didn’t give a fuck about anything. When I was drunk I would try to be as offensive and mean as possible for no reason at all.

Yet despite all this posturing I could never bring myself to eat meat. There was still something inside me, some refusal, that wouldn’t die no matter how hard I tried to kill it. That spark in me, though deeply repressed, would not go out completely.

Many years later when I dragged myself into the rooms of AA, I was forced to face the ways I had abandoned my most fundamental values and had tried to become like the people who abused me. I was filled with brutal shame. I seriously considered killing myself because without the drugs and alcohol there was nothing left but to face the pain and horror: both of what had been done to me and of what I had done. I could not claim innocence. I could not draw a line with the good guys on one side and the bad guys on the other, while feeling safe and secure in my position among the good guys. The only reason I didn’t kill myself or go back to the oblivion of drinking is because AA provided a philosophy and worldview that said I was not defined by the worst things I had ever done. I could change. I could heal. I could face myself. I could tell the truth about my enormous remorse. I could return to my fundamental values. I could work hard to make as much repair as possible and I could become a force of good in the world.

I returned to the social justice values I had abandoned and I found communities who believed in social justice too. Soon after getting sober I started to find it impossible to go on eating dairy and eggs. The disgust and horror I had been repressing returned. What was strange, however, is that despite the fact that I had found community with others who believed in social justice and compassion, others who sided with the victims against violence and wanted to make the world a kinder and more just place, none of these people were vegans. Not only were they not vegans, but they had elaborate “social justice” reasons for objecting to veganism. They kept bringing up racism, colonialism, disability, and eating disorders whenever veganism was mentioned. In fact, compassion for the animals was explicitly called racist, colonial, and ableist. The same mockery and contempt I had experienced toward my childhood vegetarianism was now dressed up in the clothes of “social justice.” I wanted to be in integrity and live in alignment with my fundamental values. I wanted to oppose racism and colonialism and ableism, and I also knew in my bones that the captivity and torture of billions of animals was fundamentally and inexcusably wrong.

I did not have the moral backbone or confidence to simply tell people that calling veganism racist, colonial, or ableist is absurd and makes no sense at all and is, in fact, an elaborate cover and shield for mass violence. I did not allow myself to think freely enough to point out the racism, colonial violence, and ableism of arguments which flatten political differences within identity groups and erase the long history of veganism and animal rights activism within groups who experience oppression. Instead I took the path of least resistance. I took on veganism as a “personal choice” rather than a political stance. I became a “chill vegan” who answered my own morality by refusing to eat the bodies, milk, and eggs of tortured animals, but who refused to “shame” others by telling the truth about animal agriculture. I even made a zine with a friend of mine called Complicating Veganism which promoted denial, dissociation, and excuses when it comes to facing and abolishing the mass torture of animals.

I stayed this way for many years. Whenever I mentioned veganism I did so by stripping it of its moral and political significance. I repeated propaganda that allows leftists to claim to care about liberation and justice while treating sentient beings as property. I even bought into ideas that health and empowerment and maybe even trauma recovery can be found in consuming the bodies of tortured animals; I just personally couldn’t “stomach” it myself. I denied the obvious connections between sexual violence and child abuse and animal agriculture that I had always known in my bones. I claimed to fight for survivors while allowing people around me to justify the mass rape and sexual torture of animals on the basis that they are not human and therefore can’t be raped.

I see now that far from returning to my fundamental values, I was still chronically betraying them. I was still actively participating in a culture that normalizes the torture and sexual torture of billions of sentient beings. I was allowing the leftists around me to feel as comfortable as possible in their total hypocrisy. I was allowing people to pretend that eating disorders (which are the direct result of trauma, usually sexual trauma) could be healed by taking part in mass sexual violence. I was pretending that veganism is a personal choice which means pretending that taking part in the torture of sentient beings is also a personal choice.

It is not a personal choice. It is wrong.

To be continued.

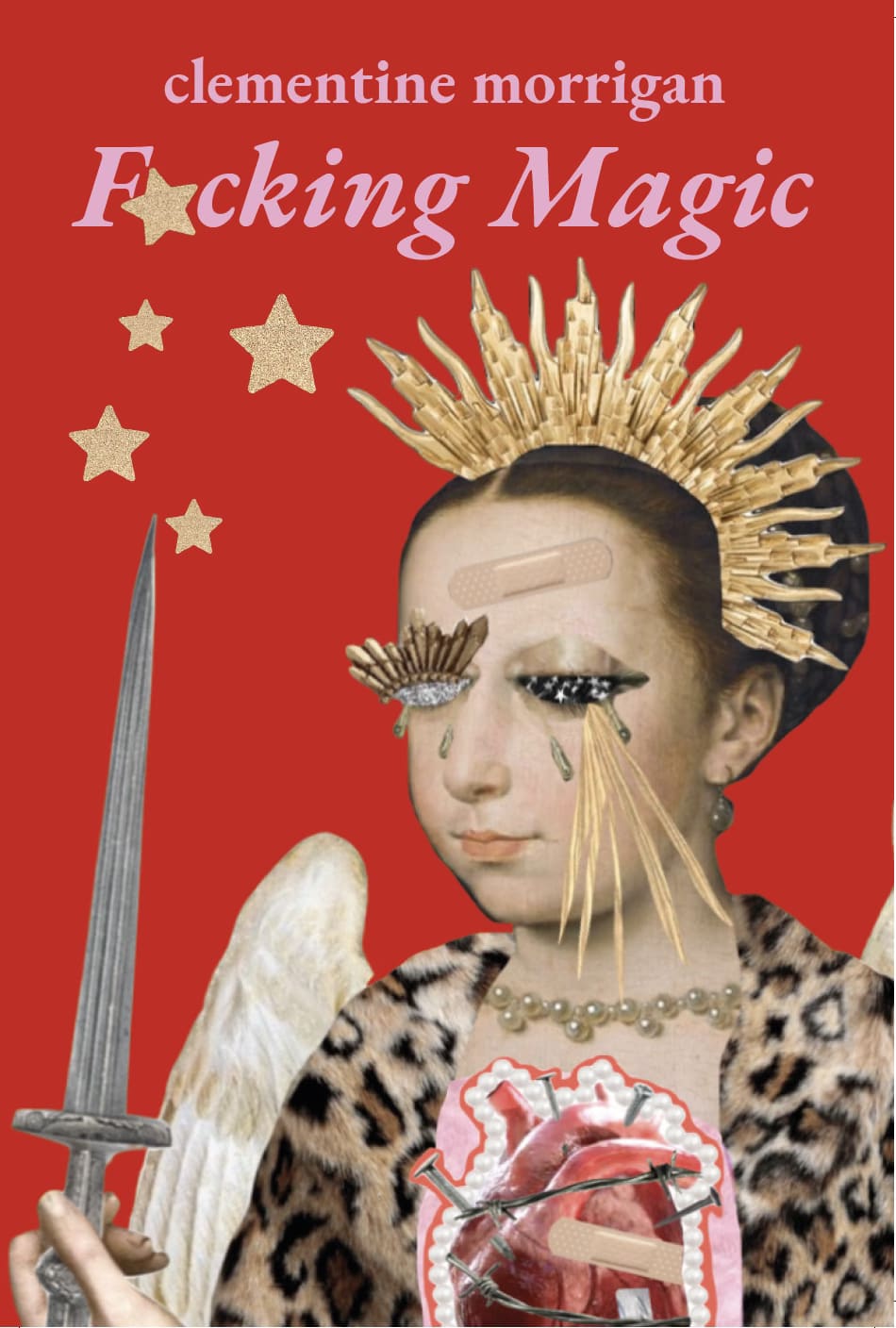

Clementine Morrigan is an underground writer, cultural change maker, and brazen truth teller. She is the author of numerous zines and books, including the cult classic zine Love Without Emergency, which will be released as book with Microcosm Press in 2026. Her popular zine series Fucking Magic was released as a book with Revolutionaries Press in 2025. She co-hosts the podcast Fucking Cancelled with Jay Lesoleil. Her work is known for its unflinching engagement with taboo and difficult topics.

“F*cking Magic is a collection of 12 zines originally hand-made by Clementine Morrigan and posted throughout the world. From alcoholism to sobriety, surviving incest to BDSM, throughout the seasons and many iterations of becoming, Morrigan leans into the darkest and most vulnerable parts of her life in this cult coming-of-age memoir that speaks to taboos and universal truths.”

Fucking Magic is out!! I am so excited!! If you care about my work, the most impactful thing you could do is to contact your local indie bookstore and ask them to stock this book. You can also order it here.

only tangentially related, but if anyone could recommend a “how to go vegan when you have an eating disorder” guide that actually works, I’d be very grateful. I haven’t been able to restrict my food intake in any way (be it diets, veganism, vegetarianism, intermittent fasting, “I only avoid beef”, veganuary, “only vegan on mondays”, high protein, literally nothing has worked) without a bulimia relapse. A few times, even just listening to podcasts about going vegan was enough to make me want to starve. I’ve been trying for the past ~10 years for the obvious reasons listed in this article. I am just miserable all the time, unless I do intuitive eating, which right now for me includes animal products. If there is an alternative I’d like to know it.